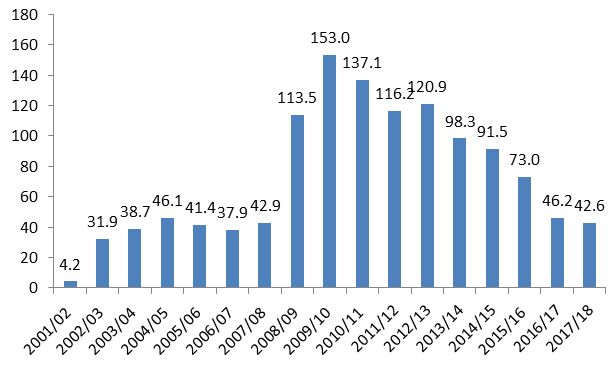

UK borrowing has fallen back under pre-financial crisis levels. Now the government needs to deal with long-term problems instead of increasing spending.

Although UK net borrowing has fallen to its lowest point in over a decade – only before the financial crash of 2008 was the deficit lower – the chancellor must refrain from using lower than forecast borrowing as an excuse to ramp-up government spending.

Despite the positive news, borrowing remains roughly at the same level as when then chancellor Gordon Brown ballooned spending between 2001 and 2005.

Even though the government only borrowed £42.6 billion ($59.5 billion) in the 2017 to 2018 financial year, borrowing is still high compared to pre-recession levels.

UK government borrowing since 2002

Dealing with an ageing population at a time when birth rates are historically very low means in future decades raising money through taxation to pay for pensions and the care many will require is set to become an increasingly difficult bill to pay.

Other major challenges, such as student debt and an ageing population, must also be confronted.

Not only that, pressure to increase spending on public services and public sector pay is enormous; but so would be the bill if urges to spend were surrendered to, driving debt levels soaring again.

It is now widely accepted that many graduates will pay their student debt before it is wiped clean after 30 years, leaving the government with a major problem to solve.

Borrowing to please headline writers in the present would make funding efforts to solve long-term problems harder, placing in jeopardy the hard-won reputation for economic prudence this government has acquired among leading financial institutions.

Increasing public spending now (thus increasing the deficit) would leave the government with a constrained list of options when the next crises strikes than would be the case if borrowing was kept on a tight leash.

This is important. For the first time in 16 years day-to-day spending is being covered by taxation.

With that in mind, the chancellor should resist urges from opposition parties to increase spending; the days of sky-high deficits should be treated as an exception, not the new normal.

Clichés aside, ensuring debt remains under control now is a much wiser strategy than increasing spending simply because the opportunity has arisen to do so.

Since the end of the Second World War, the UK has suffered seven recessions. Were another one to strike at a time when the deficit is inflated, the economic situation would almost certainly turn very nasty indeed.