In December 2020, Communications Minister Paul Fletcher formally declared the National Broadband Network (NBN) “built and fully operational”. On top of that, it was suggested in an Australian Financial Review (AFR) interview that an acquisition by another telco, possibly Telstra, was not off the table as the mode to privatization, a U-turn from previous comments made in 2019.

As rumours abound about a potential sale of NBN Co to Telstra, it is no secret that Telstra’s CEO Andy Penn had long held designs on NBN Co.

However, Australian legislation prevents vertical integrated telcos from owning NBN, which was what Fletcher had been alluding to when he had dismissed such a proposition.

“In other words, somebody who delivers retail telecommunications services cannot own NBN. That’s baked into the legislation,” he said.

Can Telstra sidestep NBN legislation?

It appears that there may be a legal workaround this limitation and Telstra is doing exactly just that through a restructuring that will see its business split into four businesses to be held by a holding company – InfraCo Fixed to own passive infrastructure, InfraCo Mobile to own the mobile tower assets, ServeCo to take the retail arm and another entity for its international business. The entity most likely to acquire NBN Co was identified as InfraCo Fixed.

However, it was reported by AFR that Penn had admitted in an interview that Telstra had to go further if it wanted to be allowed to buy NBN Co.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataTelstra’s competitors were expectedly incensed by Penn’s comment, especially Optus. A sense of betrayal is expected if such a deal was allowed to go through. NBN Co was originally formed to break the vertical monopoly that was created when Telstra was privatised in 1997, leaving other players dangerously dependent on Telstra to offer fixed line services.

In 2011, both Telstra and Optus signed an agreement to transfer ownership of a good portion of their networks to NBN Co for AU$11 billion and AU$800 million respectively. For everything to fall into the hands of Telstra would leave Optus dangerously disadvantaged. TPG Telecom, now merged with Vodafone Hutchinson Australia (VHA), would be the only serious rival to Telstra, never being part of that deal with NBN and having held on to its own nationwide fixed network, which it amassed over the years through the acquisitions of various ISPs including iiNet, Chariot and AAPT.

As various ownership models are being considered for NBN, there are better options out there to an acquisition by Telstra, which would not compromise the open access model and maintain the fair competitive environment it was intended to create.

The Singapore approach – business trust

Singapore’s Next Generation National Broadband Network (NGNBN), adopted a similar separation model where the active infrastructure was designed to be separated from the passive infrastructure. The entity, originally named OpenNet, was then sold to Singtel wholly-owned subsidiary NetLink Trust, but was deployed by rival telco StarHub through a subsidiary Nucleus Connect.

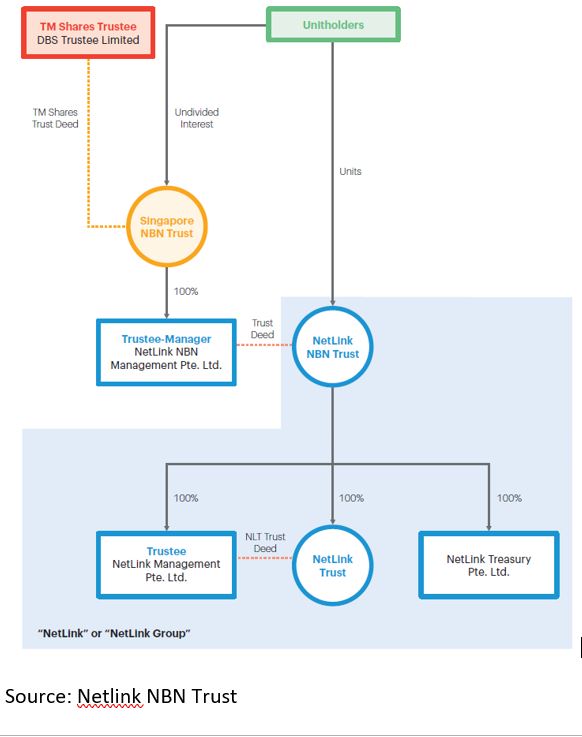

An IPO was selected as the mode of privatisation and a complex three-tiered trust structure was developed to ensure that no dominant telecom operator could take control of the company. Netlink Trust would be held by Netlink NBN Trust, and the trustee manager of Netlink NBN Trust would be held by Singapore NBN Trust of which the deedholder is Singapore’s largest bank, DBS.

After Singtel pared down its stake in Netlink NBN Trust to below 25% following an IPO in 2017 due to regulatory requirements, this meant that following 2017, there is no dominant shareholder in Singapore NBN trust.

For NBN to reach a similar end-state, NBN would need to be an attractive asset to price well in the IPO market. NBN Co may need to be carved out into an “urban” NBN Co, consisting of the more profitable major urban areas and fibre backbones for privatisation, and a “rural” NBN Co, which may have to be retained by the government for social reasons. Usually, rural broadband coverage is supported by a universal service obligation fee levied on all telecommunication companies. This would be similar to or require modifications to the Regional Broadband Scheme which was implemented only January 2021.

Unlike Singapore, which has the financial heft of its sovereign wealth fund Temasek and it portfolio company Singtel to intervene, safeguards need to be put in place so that a hostile takeover might not be an issue for the publicly listed NBN Co.

The New Zealand approach – carve out to non-telco players

New Zealand, which faces similar geographical challenges but has had a very successful execution of their national broadband network, started off with two separate programmes, the Ultrafast broadband (UFB) Initiative and the Rural Broadband Initiative (RBI), both of which are managed by Crown Fibre Holdings (CFH), an entity established by the government.

Telecom NZ, the New Zealand counterpart to Telstra, was forced to undergo a demerger into Spark, which would own the operations, and Chorus, which would inherit the passive infrastructure, as a precondition for participation in the UFB deployment projects. Chorus would subsequently become the cornerstone company to design and build the fibre network. However, three other Local Fibre Companies (LFC) were also selected to form joint ventures with CFH for deployment of UFB across various regions; two of which – Northpower & WNL – come from power companies, while the third was an ISP established by Christchurch City Council’s investment arm.

Under the commercial model employed in the joint venture, the CFH joint venture starts out as 100% CFH owned, but the commercial partner’s share in the venture increases as commercial uptake proceeds, eventually privatising the entity automatically and completely. This mechanism meant that the UFB resulted in a competitive environment with four private sector players, albeit with regional monopolies.

Scrapping NBN legislation would disadvantage smaller players

To achieve a similar end state, Telstra’s restructuring must go further to carve out InfraCo Fixed into a separate fiberco that provides only wholesale access and that Telstra does not have control over. Meanwhile, NBN Co should be parcelled out into sections, with fibercos, such as the fully divested InfraCo Fixed, and non-telco players such as utility companies and private equity firms allowed to participate, with the precondition of not having a retail telco business in Australia.

Another simpler and less convoluted privatisation approach would be to scrap the legislation barring vertically integrated telcos from taking ownership of NBN and to have all three major telcos take non-controlling stakes into NBN. Such is the case with the creation of China Tower from China three major incumbent telcos in 2014. However, this may then disadvantage smaller players such as Superloop, Aussie Broadband, MacTel, and potential future entrants.

Certainly, the Singapore and New Zealand models are not the only possible outcomes for NBN Co’s eventual privatisation, but their success hitherto warrants further study.