Tech giants like Twitter, Facebook and Google claim to be champions of freedom of expression and other democratic values, but when faced with requests from autocratic regimes to remove content, they often comply.

Should they acquiesce to such demands? Does the law make it impossible for them to refuse?

Facebook’s community guidelines do explain that the social network will make content unavailable if it violates local laws after “careful legal review.”

Governments also sometimes ask us to remove content that violates local laws, but does not violate our Community Standards. If after careful legal review, we find that the content is illegal under local law, then we may make it unavailable only in the relevant country or territory.

Twitter’s policy is much the same:

With hundreds of millions of Tweets posted every day around the world, our goal is to respect our users’ expression, while also taking into consideration applicable local laws. If we receive a valid and properly scoped request from an authorised entity, it may be necessary to reactively withhold access to certain content in a particular country from time to time.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Company Profile – free sample

Company Profile – free sampleThank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData

Google explains that the reasons why governments issue requests vary:

Some requests allege defamation, while others claim that content violates local laws prohibiting hate speech or adult content.

The search engine admits that governments sometimes use removal requests as a way to exert power and silence dissenting voices.

Often times, government requests target political content and government criticism. Governments cite defamation, privacy, and even copyright laws in their attempts to remove political speech from our services. Our teams evaluate each request and review the content in context in order to determine whether or not content should be removed due to violation of local law or our content policies.

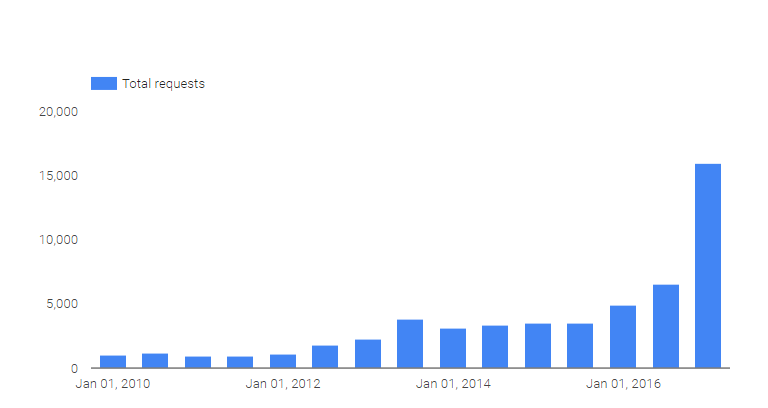

The total number of requests sent to Google between 2010 and 2016

However, with content removal requests from governments on the rise, is it possible for teams to dedicate sufficient time to each one?

Russian state bodies sent the US search engine over 13,200 requests to remove content between the last day of 2015 and the first day of 2017, according to Google’s transparency report.

The problem with local laws

If a government request relates to content which is in violation of local laws, technology companies have little choice but to take that content down, Mark Grossman, a New York-based technology lawyer tells Verdict:

There’s a certain arrogance both in Britain and the US that our laws apply everywhere and they don’t. Can you imagine a Russian company coming to the US and taking the position that we have to comply with Russian law, not American law? We would say they are insane.

So companies face a dilemma — agree to local laws or lose out on a market.

Making that decision requires an understanding of local laws, which are difficult to make sense of and vary dramatically from region to region.

Peter Micek, the general counsel at Access Now, a global digital rights organisation tells Verdict that technology firms face a challenging task when it comes to navigating domestic laws.

There’s local laws that are vague, there’s local laws that are too broad, there’s local laws that don’t comply with human rights commitments that the governments themselves claim to abide by.

Technology companies often avoid taking on these complex legal battles, instead surrendering to governments with questionable human rights records.

“No government feels that they don’t have jurisdiction over Facebook,” a source who advises some of the biggest global technology companies tells Verdict.

In 2014, Twitter agreed to demands from the Russian and Pakistani governments to remove content from its platform, shying away from confrontation.

The microblogging service blocked the account of an ultranationalist Ukrainian group from users in Russia and censored content in Pakistan after a bureaucrat’s complaints that certain posts were “blasphemous.”

In February this year, Vietnam demanded that Facebook and Google’s YouTube crack down on “toxic” anti-government content.

The communist regime pressured local companies to withdraw from their advertising contracts with the social media firms until the issue was resolved.

Two months later, Facebook announced its commitment to work with the Vietnamese government to help facilitate content removal.

“Facebook will set up a separate channel to directly coordinate with Vietnam’s communication and information ministry to prioritise requests from the ministry and other competent authorities in the country,” the social network said in a statement issued at the time.

Facebook declined to comment on the issue when approached by Verdict.

Commercial interests

In Vietnam, Facebook and YouTube account for two-thirds of the country’s digital media market share, according to local agency Isobar Vietnam.

In Pakistan, where Facebook has also engaged with the authorities when it comes to removing content, the social network has about 25m to 30m active users.

“We see it very positively that at the highest level Facebook has responded and takes this issue [of blasphemous content] seriously.” Pakistan’s interior minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan said in March.

So do commercial interests play a role when companies decide whether or not to abide by local laws?

Although the legal restrictions can be difficult for the tech giants to circumvent, the likes of Facebook, Google and Twitter have come under attack for making money their top priority.

Gabrielle Guillemin, a senior legal officer at Article 19, a UK-based human rights organisation tells Verdict:

These companies clearly have a commercial interest — if they want to maintain operations in a particular country with a large market, they will want to accommodate the demands of the government there.

Upholding freedom of expression is no longer paramount, she adds:

These platforms have become so big, they want to conquer more markets and get more users.

However, Micek disagrees.

It’s not just about commercial gain. Of course, these tech giants are hyper capitalist companies, but they do push back against government requests. It is in their interests to let users enjoy their platforms openly and without unreasonable restriction. They care about gaining the long-term trust of their user base and safeguarding their reputation.

Powerful governments – arrests, ISPs, and extra territorial takedowns

The difficulty is that, even when technology companies say no to regimes, government officials find other ways to get what they want.

“It’s a game of chicken,” says Alan Davidson, a fellow at the New America Foundation, a think tank and civic enterprise.

“Yes, companies have to draw lines, but they run the risk that a government will then ban their service or arrest their employees. There have been a number of situations where that’s been the case,” adds Davidson, who was the first director of the digital economy at the US Department of Commerce and a former director of public policy for Google in the Americas.

When YouTube refused to comply with requests to remove a series of anti-Islamic “Innocence of Muslims” videos in 2012, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sudan and Pakistan simply took the platform offline.

Months later, there was another incident where government officials took matters into their own hands.

Police in Sao Paulo detained Google’s Brazil boss Fabio Jose Silva Coelho after YouTube, the video platform owned by the search engine, refused to take down footage deemed to be offensive by the authorities.

According to a regional judge in Brazil, the videos “slandered insulted and defamed” Alcides Bernal, a mayoral candidate in the western city of Campo Grande, which was a violation of the country’s local election laws.

When ordering the police to make arrests is not feasible however, governments elicit support from elsewhere.

“Governments are getting much more sophisticated. They’ve realised that if they get resistance from Google or Facebook, they can go to the providers of the network infrastructure on which those companies rely,” a source close to the technology companies, who spoke on condition of anonymity tells Verdict.

Turkey routinely blocks access to social media sites using internet service providers (ISPs).

Following the arrests of at least 11 pro-Kurdish politicians in November 2016, two ISPs TTNet and Turkcell shut down Twitter, Facebook and YouTube at the request of the Turkish government.

“Internet restrictions are increasingly being used in Turkey to suppress media coverage of political incidents, a form of censorship deployed at short notice to prevent civil unrest,” the internet monitoring group TurkeyBlocks wrote in a blog post published at the time.

Perhaps the most worrying form of censorship is when governments want the removal of content to extend beyond their country’s borders, in what are known as extraterritorial takedowns.

Gus Rossi, the director of global policy at Public Knowledge, a non-profit promoting freedom of expression and an open internet is concerned that requests of this kind will become increasingly common:

Governments trying to impose their national values outside national borders is a big problem especially because if one country is allowed to do it, it sets an example for other countries to do it too.

If you can, I can

Over the past year, technology companies have continued to comply with the majority of government demands.

Two incidents are noteworthy in that they highlight the reluctance of platforms to fight back.

Last month, the photo messaging app Snapchat, owned by California-based technology company Snap Inc blocked access to Al Jazeera‘s content on its platform because the Saudi government asked it to.

Mostefa Souag, Al Jazeera‘s acting director-general said at the time that Snapchat’s decision gives the green light to other regimes that it is acceptable to impose their views on technology companies:

“We find Snapchat’s action to be alarming and worrying. This sends a message that regimes and countries can silence any voice or platform they don’t agree with by exerting pressure on the owners of social media platforms and content distribution companies.”

A source with first-hand knowledge of the complicated relationship between governments and technology platforms agrees.

“If the government of Vietnam sees companies willing to negotiate with the Saudi government, then they are going to feel entitled to the same terms and conditions of negotiation. That dynamic doesn’t just play out between governments that we would consider non-democratic,” he says.

Indeed, non-democratic countries are not alone in setting worrying precedents.

Defamation of religion, for example, is prohibited in Germany, a western democracy.

“These laws aren’t consistent with international standards on freedom of expression but Germany is a democratic country, so how can you then say no to Pakistan?” Guillem explains.

In March, when Facebook agreed to remove 85 percent of all “blasphemous and objectionable” content in Pakistan, the social network did so because it received a handful of complaints from government officials.

It is unlikely that countries like Russia and China will ever make it easier for US technology companies to operate without heavy censorship.

“The Chinese government and to some extent the Russian government spend billions of dollars to essentially create their own internet bubble,” a source close to the technology companies says.

However, there is hope that “the swing states, where governments have not decided to completely censor the internet” will show a greater willingness to comply with international human rights norms.

Why? Because technology platforms help a country’s economy to function. They’ve become indispensable.

“As these platforms continue to broaden their offerings, whether it’s helping people communicate with their loved ones or facilitating make mobile payments, it will become harder for governments to crack down on tech giants without harming their economies,” she adds.