Following the London Science Museum’s screening of the new Apollo 11 documentary on Wednesday, the UK’s first British cosmonaut and the first woman to visit the space station Helen Sharman held a two-way interview with veteran science broadcaster James Burke. Verdict was there and witnessed first-hand some space secrets not every rocket fan may have previously known.

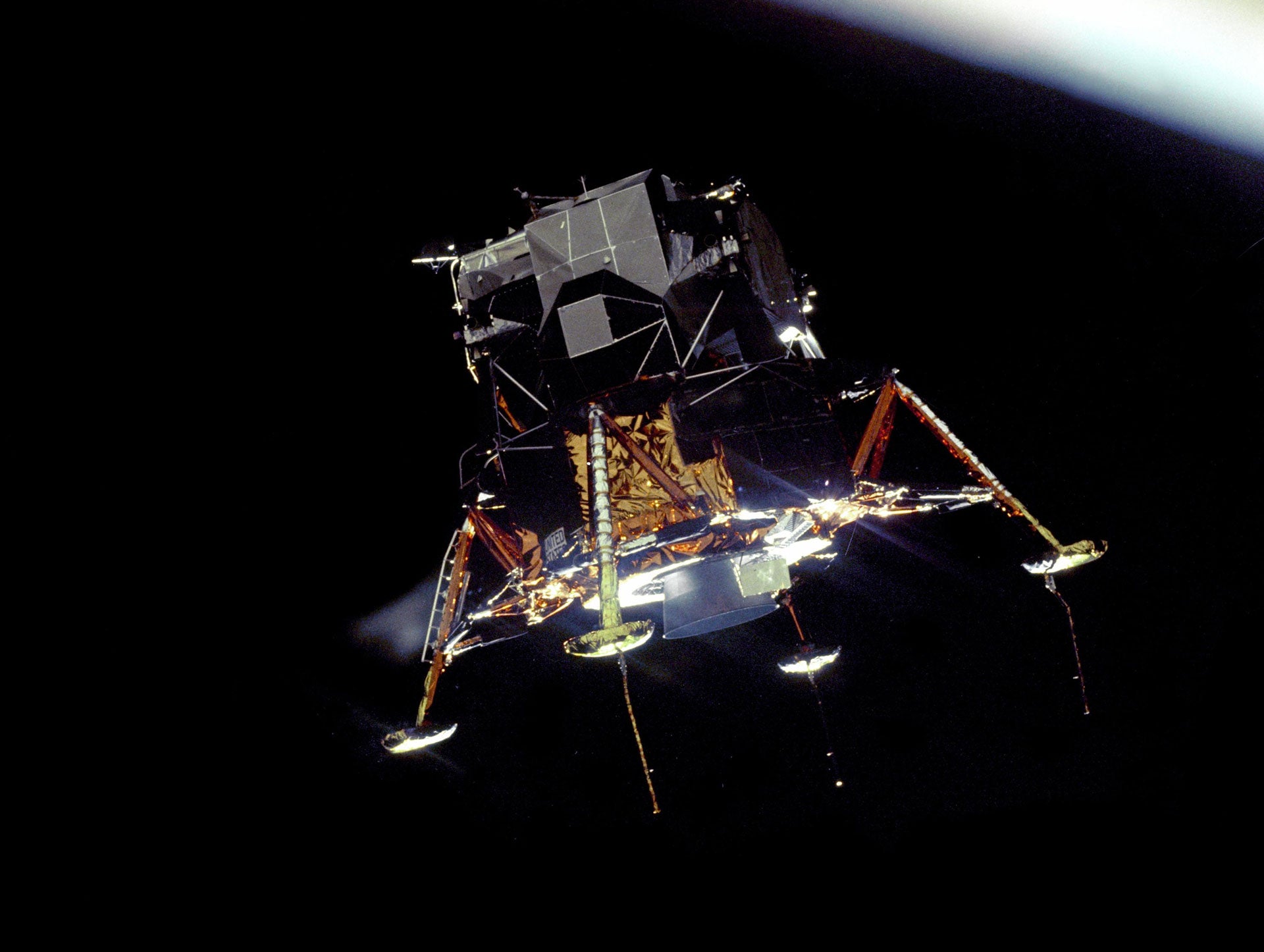

The Apollo 11 film brings together never-seen-before video and audio footage of the mission that launched from Kennedy Space Station on 16 July 1969 and saw astronauts Michael Collins, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin safely splash down on 24 July. Edited with a minimalist musical soundtrack but no commentary, the IMAX showing, in particular, immerses the audience with full-vision images and bone-shaking booster rocket sensation.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

Before the era of regular science news correspondents, James Burke had appeared on popular science TV show Tomorrow’s World and was seconded to report on the Apollo programme. He became as well known for his impeccable timing on live broadcasts and being part of the first film crew to record on the “vomit comet” sub-orbital zero-G simulation flights, which remain popular today via YouTube snippets. Helen Sharman interviewed him about his experiences and shared some of her own spacefaring adventures after the Science Museum screening.

James Burke on Apollo 11’s scariest moments

“What Mission Control knew and did not say at the time was that as the lunar module and the command module separated in lunar orbit, there was a tiny amount of excess air in the docking tunnel, and they afterwards described it like a champagne cork popping. It gave the lunar module a little extra impetus over what it was supposed to have.

“And that meant when they went down they were four miles beyond the landing site that had been so carefully photographed and prepared by Apollo 10. Everybody knew as much as they could about that site, and now they weren’t going to land there. The only clue we got was I heard Armstrong in the last few seconds say ‘boulder’, and there weren’t supposed to be any.

“He had come in over a football pitch-sized crater filled with boulders he described later as being as big as cars, and he had to decide what to do, to go to the other end of that and see if there was any way to land. He did, and he landed, after 240,000 miles in three days, with just 19 seconds of fuel remaining. That’s what you call nerves of steel. And that’s why we were scared. Because we didn’t know whether things like that were going on. And our job was to deal with it if it did. But that was like dealing with something for which you’ve had absolutely no preparation, because you didn’t think things were going to go wrong; NASA said we’ll do our best.”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData

Helen Sharman on why astronauts don’t get scared

“We are trained to cope with all the things that you can anticipate, and that’s what the simulators are for. You train with the plan A and then there’s a backup plan, and plans C and D just in case. But during Apollo 11, it was just the knowledge and Neil Armstrong’s skill in actually flying that lunar module that enabled them to be safe in the end, because he couldn’t possibly really be prepared for all of that.

“We have the theoretical training so that we can think our way through situations, because nowadays it’s less reactive and real seat-of-the-pants flying, that situations tend to be much more complex. So it requires teams of people to think about how you’re going to what you need to do, decide who’s going to do what, and then get on and do it.

“I was never scared, and I don’t think I’m particularly brave, or a particularly high risk-taker. I think it’s because we are scared of the unknown, so if the training is so very, very good there is no unknown to be scared of. I never thought I would die, or I wouldn’t have gone!”

James Burke on the BBC nearly missing the moonwalk

“As chief geek, my job was to read this flight plan second-by-second and stay with it. And they landed, and they went through three periods, as they were saying yes, you’re right, you’re safe, you can stay for the next period, and then finally, the third period, and now you can take the moonwalk.

“And at that point, the plan was that they would prepare for sleep, set up a couple of hammocks and they would have about four hours’ sleep, and then they’d wake up and then they’d get out, and that would allow us to have a good sleep too. At about half-past 10 at night, we went off the air.

“But I’d heard them talking stuff from five pages further on in the flight plan. I wasn’t being clever, I just went five pages further on and they were doing this stuff, which is what you do when you’re going to get out. So we were off air and I said to the people in the control gallery, they’re going to get out.

“It was the first time for the BBC to be staying up all night. I mean, big deal, they’re on the Moon. And we’re going to be staying up all night! So we went back on air at 11 o’clock and stayed on the line, and it was three minutes before the moment.”

Helen Sharman on being the first British woman in space

“I was accepted as a friend, the Soviets were very proud of their country, but particularly the space programme, so they wanted to show it off; they just took us into their bosom as a part of the whole programme. I think I only really felt foreign when I was recording for British media.

“And then on the launch pad – I’d realised before that I was a British astronaut – realising quite what the significance of this was. It wasn’t just me going into space, because I thought it was going to be fun, this was actually a first British space mission. So it was some kind of responsibility there, so I did feel a bit responsible as a citizen.”

Helen Sharman on why she wore a frilly pink number in zero gravity

“This was Alexei Leonov’s idea. He’s known as the first spacewalker, but he’s actually my boss in Star City, so he’s in charge of all the foreigners. Great joker, lovely personality, lovely man. But at the launch site in the quarantine period, he decided upon himself without any words to me, he’d go off to the local dressmaker, he’d choose some material – frilly pink, his own design, and have them make this outfit. So it was shorts rather than a dress because we were in space, but it also frilly and very Russian, of course. He said you have one secret from your commander and it’s okay because I say you can have it.

“This spacesuit has been designed, made to measure with the pipes and so on, a bit uncomfortable. But he says we’ll just shove it inside your spacesuit. And then when you get into orbit and everything’s fine, try it on and try and do it surreptitiously, and when you actually get to the space station, you’ll have a special dinner, and then you can get it out and put it on. And it will be a great joke for everybody, it will be hilarious. And I’m thinking, “Thanks…?”

“The next day we had our dinner, I got into my pink frilly thing and Sergei wore his tie, which floated out horizontally.”

Read more: Watch: Apollo 11 landing reconstruction shows Armstrong’s view for first time