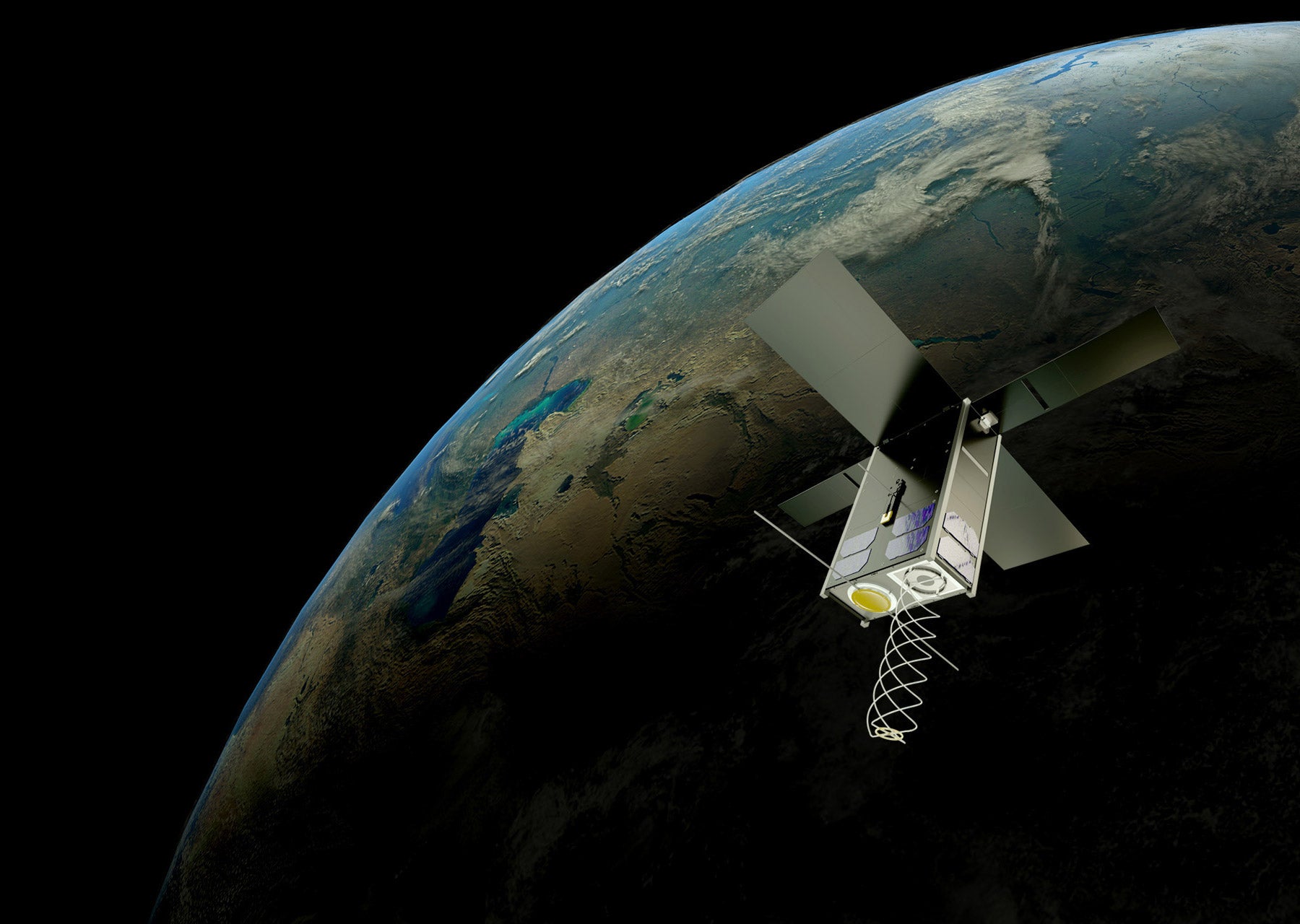

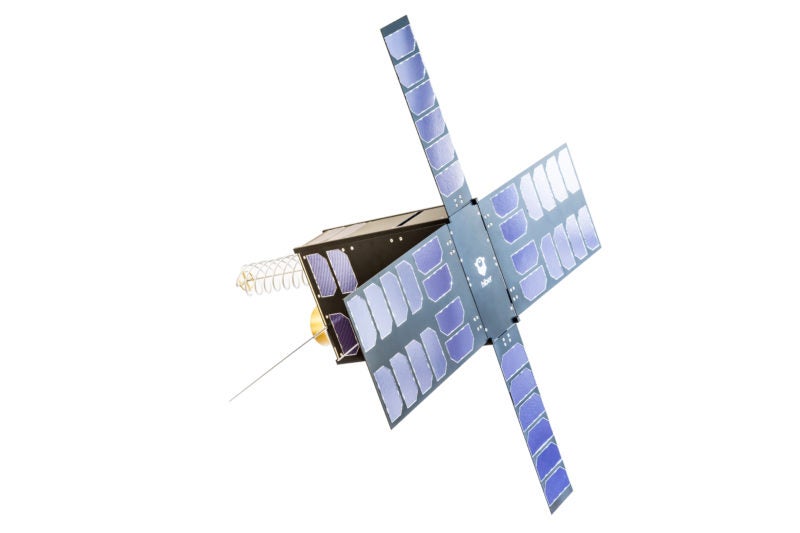

Hiber nanosatellites might be small, but the Dutch space startup has big ambitions: to provide low-cost, low-power internet connectivity to internet of things (IoT) devices anywhere on the planet.

The firm launched its first two nanosatellites in November 2018. It expects the network to go live for its partners – which include the British Antarctic Survey and non-profit EduClima – in the next two months.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

Hiber is focused on three markets: agriculture, tank and silo monitoring and logistics. The solar-powered satellites will collect data beamed up from a modem connected to IoT devices and relay them back to Earth in places where internet connectivity is poor or non-existent, such as rural areas in Africa.

Crop sensors, for example, can gather information about the levels of moisture in the soil, humidity and temperature.

“Wi-Fi, or any other fibre solution, they only cover about 10% of the world,” says Hiber’s co-founder and director of business intelligence, Coen Janssen.

“And that’s why satellites are actually the way to go if you want to expand beyond that 10%.”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataTo get these updates, it costs “just a few euros a year,” says Janssen, who has previously worked for NATO exploring the future of nanosatellites.

“The farmers get an update on what to do on the field, whether that’s irrigation, taking care of the crops with nutrition, this kind of information.”

This works out to farmers getting “three or four times more yield out of their crops,” he adds.

Launching Hiber nanosatellites to space

Getting to space is extremely expensive: “One of the bottlenecks to actually get to space is the launching market,” says Janssen.

The infrastructure required to send a rocket to space costs hundreds of billions of dollars. Before private space companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin reduced the cost of sending rockets to space, it cost hundreds of millions of dollars per launch.

Hiber works with these commercial ventures, renting one of the “leftover areas” of a SpaceX rocket. At a cost of “about €50,000 per kilogram”, the total cost of launching one shoebox-sized Hiber nanosat to space is about “half a million” euros.

Once the rocket’s upper stage deploys, the nanosat is propelled from a “deposit box” by a spring. There is no jet propulsion to align the small satellite in orbit – it is all about timing, with Newtonian physics dictating that the satellite is captured Earth’s gravity into orbit around 600km above Earth.

Moving at a velocity of about 7km per second, each nanosat circles the Earth a total of 16 times a day.

How nanosats gather data

Step one is collecting the data on Earth, whether that’s on a farm or the middle of the ocean.

The data packet – around the size of a tweet – is sent to and stored in a Hiber modem located near the IoT devices.

Most of the time this modem is in sleep mode. This keeps power usage down to a minimum, which in turn brings down costs.

This hibernation approach is what gives Hiber its name. “The modem is in hibernation 99% of the time,” says Janssen.

When the satellite flies over the modem, it wakes up and sends the data up to the nanosat, then goes back into hibernation. The nanosat then sends the data back to Hiber’s ground station on Earth.

“Then the data is available via a data repository for the end customers.”

A growing nanosat industry

Falling costs of space launches and an ever-increasing demand for connectivity has to an expanding small satellite industry. Companies such as Sky and Space Global, OneWeb and Astrocast are all offering internet connectivity to areas with limited coverage.”

Tech giant Amazon also has plans for space with a proposed constellation of 3,263 satellites in low Earth orbit to provide fast internet to consumers.

But Hiber is focusing on its niche of providing global IoT coverage at a low cost. And long term, it aims to launch more nanosatellites, so that it can go from a “once-per-day to a once-per-hour global service”.

Read more: Nanosatellite breakthrough “completely changes the costs of space exploration”