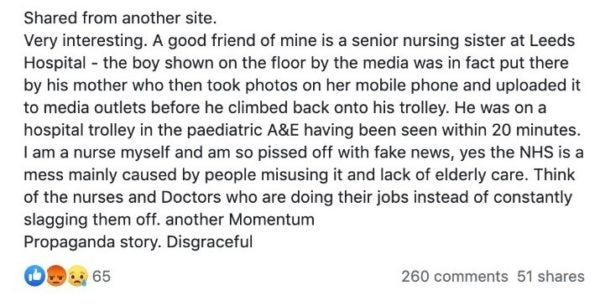

There is a very popular senior nursing sister at Leeds General Infirmary. Or so social media would have you believe, after posts seeking to discredit a picture of a sick child lying on a hospital floor went viral.

The Facebook and Twitter posts, claiming to be from a “good friend” of a “senior nursing sister at Leeds Hospital”, began circulating Monday evening. The identical posts attempted to cast doubt on the family of four-year-old Jack Williment-Barr, who was admitted to hospital with suspected pneumonia.

Another post followed. This time, scores of users all claimed to be a “former paediatric A&E and PICU nurse” and again sought to discredit the Williment-Barr family.

The false Leeds hospital story has been shared thousands of times on social media, despite Leeds General Infirmary confirming that there was a shortage of beds and apologising to the family.

So where did this fake story come from, and how did it spread so quickly?

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe amplification of false narratives

According to the Guardian, the false story was initially spread by a hacked Facebook account. It was then cut and pasted by social media users and then amplified by accounts with large Twitter followings, including Telegraph columnist Allison Pearson and former England cricketer Kevin Pietersen.

According to researcher Marc Owen Jones, who studies the spread of false information on social media, Pearson was instrumental in amplifying the low-level chatter spread by smaller accounts. This amplification resulted in more users cut and pasting the false message to share with their friends.

8/ It's 3.20 am here and I'm tired but I'll wager @allisonpearson is perhaps the most influential proponent of the faked floor theory. Stay tuned for her expose in the telegraph. I hope she interviewed the senior nursing sister! Night all ! https://t.co/FDxkiXzhnr pic.twitter.com/ZfH4u1jUzQ

— Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones) December 10, 2019

Did bots help spread the fake Leeds hospital story?

There is no clear evidence that bots – automated accounts – were used to spread the fake Leeds hospital story. Jones told Verdict that it’s impossible to know if the accounts used were “bots per se”, adding that they “could be sock puppets” – an online identity used by a real person for the purpose of deception.

“But without a smoking gun we do not necessarily know whether the tool is automation or more manual – [which is] arguably irrelevant,” says Jones.

That’s because the end result is the same; the disinformation campaign successfully shifted the narrative away from bad publicity for the Conservative Party.

Earlier on Monday afternoon, the news cycle was dominated by Boris Johnson refusing to look at the picture of Jack Williment-Barr, before pocketing the phone of the journalist interviewing him.

Health secretary Matt Hancock was then sent to the Leeds hospital to repair the damage. Next, Conservative sources said an advisor to Hancock had been punched by a Labour activist. Video footage later showed this to be false.

“We can say definitively it’s a coordinated influence campaign perpetrated by unknown actors, but ones that want to whitewash Johnson’s mistakes,” says Jones.

Former GCHQ intelligence officer Malcolm Taylor says that the dead cat theory, in which a more sensational story is introduced to divert the conversation away from a more damaging one, “may be significant”.

“The picture [of Jack Williment-Barr] seems genuine and is clearly political, and so spreading doubt about its provenance is a way of deflecting from it,” says Taylor, who is now director of cybersecurity at ITC Secure.

“Pandering to the narrative”

During an election, everyone is competing for eyeballs. Each news cycle, political parties attempt to plant their flag, to make it their own, to mould the narrative. This general election, we have seen parties go to greater lengths to do so. For example, the Conservative Party’s press office changed its Twitter account name to “FactCheckUK” during a leadership debate.

While there is no proof as to who is behind the Leeds hospital disinformation campaign, it is clear to see which party benefits. Instead of talking about a sick child laying on a hospital floor and the NHS funding gap, the conversation shifted to questioning already established facts.

“We are pandering to the narrative, set by the disinformation senders,” says Jones.

For journalists, it’s a Catch-22: it is necessary to call out disinformation, but doing so can achieve the objectives of the disinformation campaign.

A Twitter spokesperson told Verdict that “platform manipulation is strictly against the Twitter Rules”. Verdict has approached Facebook for comment.

For social media platforms, preventing the spread of disinformation is an uphill, near-impossible struggle. With just two days of the general election remaining, it’s unlikely that this will be the last time such tactics are deployed on social media.

Taylor adds that data, including photographs, have the power to potentially change votes.

“The question for me is do we understand that, and accept it or wish to treat it?” he says. “And if we do wish to treat it, quite how?”

Read more: Twitter bans political ads, but has bigger bots to fry