A new report out from UK think-tank Reform has recommended a pre-funded social care system be phased in to eventually replace the current system of so-called Pay As You Go taxation.

However, some of its measures will not be easy to sell to the public.

Social care is hard to define as it covers a broad range of services. It encompasses most things the government or private sector do to help people maintain quality of life in spite of physical or mental impediments.

Social care takes care of people of all ages when they are in need or at risk, but the report from Reform focuses on social care for the infirmities and difficulties caused by old age and its recommendations address the gap in that sector.

This is for a specific reason.

Though people under 65 can be placed in need or at risk from a variety of physical and mental impediments it is not a likelihood you can easily plan for.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe infirmities of old age on the other hand are much more predictable and can be relied upon to weigh financially on the system as populations get older.

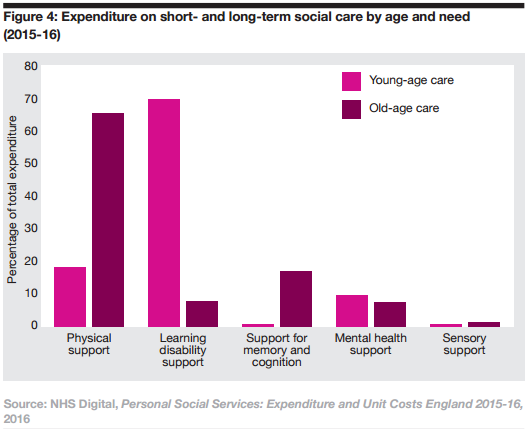

Seniors also account for the lion’s share of public spending on social care.

For these reasons Danail Vasilev, author of the Reform report, said this is an appropriate system for pre-funding.

(Image from Reform report “Social care: A prefunded solution,” 2017)

What’s the problem with social care?,

The simplest way to look at the social care problem is to imagine how all social security systems are meant to work in theory.

Over the course of our working lives we put away an amount of money in tax and national insurance at a rate calculated to provide enough money for us to be financially stable and cared for in our retirement.

This isn’t money we save into our own little accounts, rather a pool of money we can all draw from.

This all works fine if you have roughly the same amount of people entering and exiting their working age; the people on their way out are paid for by the people coming in. It’s like a national rounds system.

Sort of.

Vasilev told Verdict:

If your population is young and your economy is growing, you can make the young pay for care for the old today, [and then] you can very easily compensate them when they are old by taking taxes from the young in that period.

The system begins to fail when there are not enough people coming into the working economy to support those in retirement. And that’s exactly what has happened.

The fertility rate for women was around 3.7 in the mid-60s, in contrast to around 2.7 in 2014 (all statistics in this article are sourced from the Office for National Statistics unless otherwise stated).

We’re not having enough kids to help pay for our parents’ care.

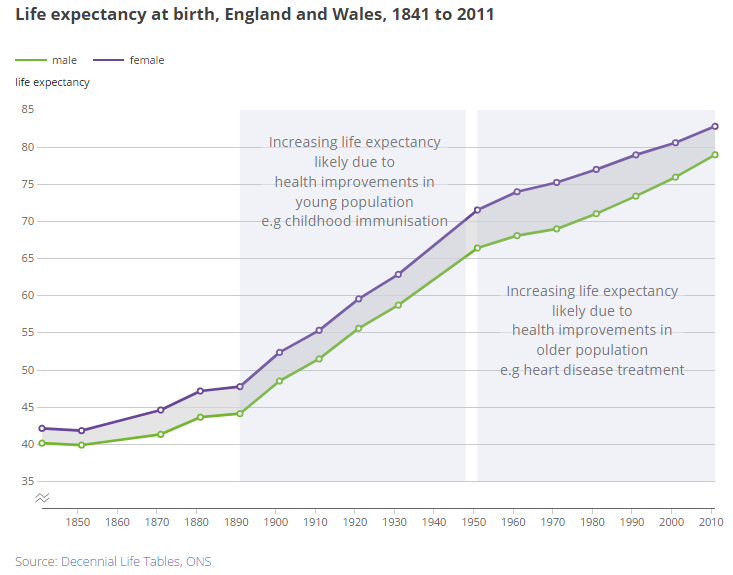

Thanks to advancements in medicine we’re also living about ten years longer than we were in 1950.

This means people will need to be looked after for longer, extending the cost. So basically you can blame this on Baby Boomers and doctors if you so wish.

It’s worse in other counties.

Japan’s over-65s for instance represent 26 percent of the total population according to the Japanese bureau of statistics.

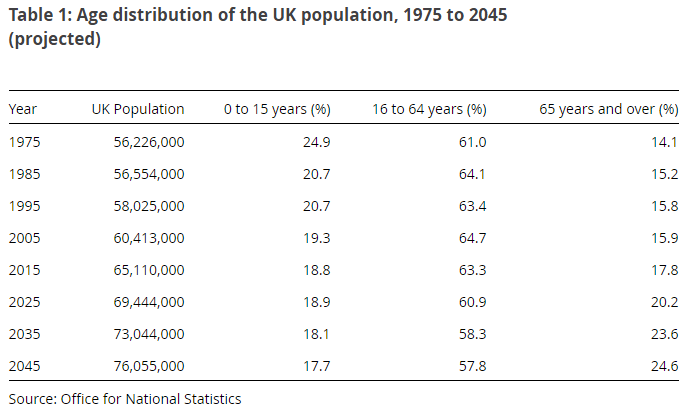

In the UK it’s sitting at an arguably comfortable 18 percent, matched by the number of under-15s.

By 2035 however the number of over-65s is projected to hit around a quarter.

All of a sudden we realised the population is ageing very quickly and this model is not applicable.

The middle section of 16 to 64 years is set to go down by 10 percent in that time, from around 63 percent to 58 percent but those under-15s, gearing up to enter the labour force, will remain steady at around 18 percent.

This means we are living longer, and the burden is only going to increase.

A need for reform?

According to the Reform report, based on estimates from the non-governmental public Office for Budget Responsibility, the cost of publicly funded social care will double from one percent of GDP (£19bn) today to more than two percent of GDP (£40.1bn) in 2066-67.

This means age-related expenditure will drive debt above 200 percent of GDP sometime in the 2050s , a level Reform said has never been seen before in peacetime Britain.

Vasilev told Verdict this rising debt, which will need to be paid back by later generations, represents a massive transfer of wealth from the young to the old.

We are now realising this model is unsustainable as the population is rapidly aging. So what we are proposing to do is to introduce a tax whereby the current young are paying for their own care in the future. They are putting aside some money which is then invested in a fund, this generates returns on the private market and once these young people are old they can draw on these funds.

The idea is that a compulsory insurance scheme would be introduced covering social care specifically.

To cover the rising social care needs of future generations Reform estimates it would need to take around £30 per month from employees’ pay while their employers would kick in the same amount.

One immediate problem with this system is it effectively means a system of double-taxation for the current generation of working young, and those about to enter the workforce, to plug the social care gap.

Youngsters would have to pay into their own fund while still funding the current system through HM Revenue and Customs’ current collection system called PAYE, something Vasilev acknowledges:

We would have to still continue to fund the current system, and if we continue to do it the way we do it now, which is through central taxation, we would be asking the young people to be paying twice.

For this system to work a way would need to be found to bridge the gap between now and in 40-odd years when today’s younger generations start drawing from their own self-funded care pools.

Reform’s proposal to bridge that gap is not the most popular of ideas at the moment.

At least, it didn’t go well for the Tories. The report said:

Pensioner households, after housing costs are taken into account, are now better off than working-age people. In this context, it is increasingly difficult to defend the 6.1 per cent of GDP that is currently spent on the State Pension and pensioner benefits.

Yes, they’re talking about the Winter Fuel Allowance.

The Winter Fuel Allowance cost £2.1bn in 2015-16, but nearly 90 per cent of recipients are not in fuel poverty and only 41 per cent of payments are spent on fuel costs.

(In case it’s unclear why this would be controversial)

That’s not the only scrapped Tory manifesto pledge they’ve gotten behind.

I think you know where this is going. The report went on:

Further generosity is delivered through the ‘triple lock’ on the State Pension. This uprating mechanism ensures the State Pension increases each year in line with the highest out of earnings, inflation, or 2.5 percent. (…) This measure is expensive – costing over £4bn a year in 2016-17 compared to earnings indexation – and is unnecessary in view of recent changes to pensioner incomes. Indeed, the additional cost to the State Pension delivered by the triple lock nearly mirrors growth in expenditure on social care in the long run.

Vasilev said drawing cash from these two sources is a temporary but necessary measure.

Tapping into the wealth of old people would be part of that transition but this would not go on in the long term. In the long term it will (just) be the extra tax we’re proposing.

The other major concern is the where the new fund will be kept.

The report recommends it be invested by private fund managers.

This could make people nervous given the volatility of the financial system.

But the report says this is the only way to ensure the money is not misused by governments looking to provide funding for their own projects.

By mandating the money remain in privately-managed funds whose only remit is to maximise profit (within predefined acceptable levels of risk) the funds would be safe from cash-strapped politicians dipping into the pool.

Nonetheless, entrusting to fund managers a nation’s ability to care for its citizens in old age will make a lot of people uneasy, and with controversial measures such as scrapping the fuel allowance and triple-lock, Reform’s proposed prefunding system is in for some serious opposition.

Dan Vasilev understands this but said radical changes are necessary to ensure future generations are not left out in the cold.

Yes, asking pensioners to fund their care directly is controversial, but this is the price to pay if we want to overhaul the system. The alternative would be to place the burden on the young generation who have been hit by a decade of subpar growth and do not have the same housing wealth as the older generations.