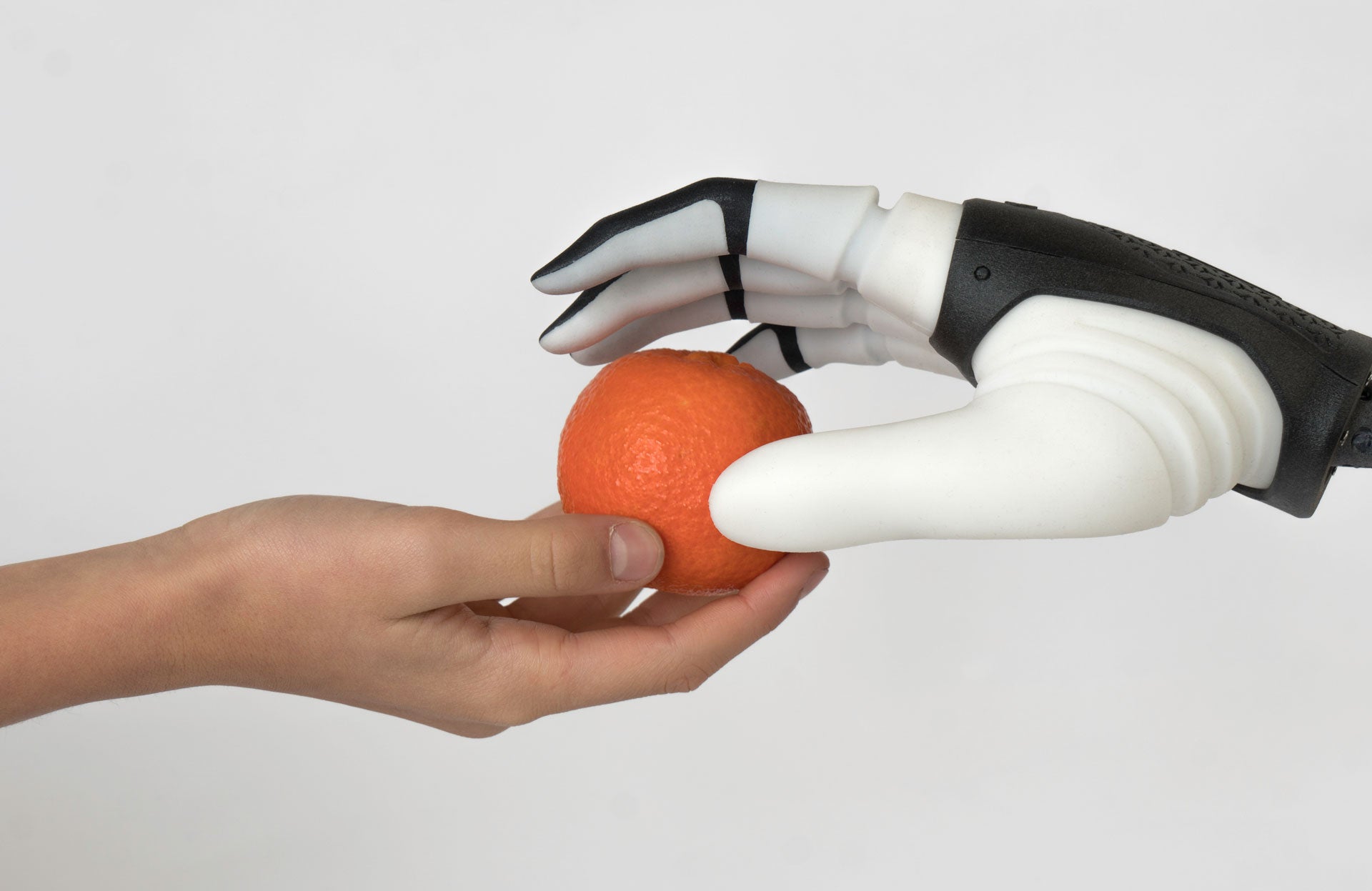

Robots are set to improve their choice of grip now a study into grasp choice has been released from The BioRobotics Institute of Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna and the Australian Centre for Robotic Vision.

Successful physical cooperation between humans and robots, in a field called collaborative robotics, could help across industries and lead to more natural interactions.

In surgery, for example, a robot collaborating with a human surgeon would more effectively pass tools so that the handle of the scalpel hits their hand.

According to the study, there is a precise moment that has decisive importance in the efficiency of handing an object between actors.

Consider the decisive moment when one relay runner hands the baton to the next runner.

The researchers looked at the guiding principles behind the choice of grasp during an exchange, analysing the behaviours of a person grasping an object with the intention of passing the object on to someone else.

They considered the type of grasp and the hand placement during the handover and found that the passer grasps the ‘purposive’ part of the object, leaving the handle for the end user to receive the object and use it most efficiently.

You might recall art lessons at school, where the teacher told you to carry scissors with the closed blades in your hand so that you could pass it handle-first to your classmates.

“For robots, grasping and manipulation is subtle”

Australian Centre for Robotic Vision director Peter Corke said: “While most people don’t think about picking up and moving objects – something human brains have learned over time through repetition and routine – for robots, grasping and manipulation is subtle and elusive.”

Francesca Cini, PhD student of The BioRobotics Institute and one of the two principal authors of the paper, considered the example of passing a screwdriver handle-first.

“The aim of our research is to transfer all these guiding principles onto a robotic system so that they will be used to select a correct grasp type and to facilitate the exchange of objects,” she said.

“Collaborative robotics is the next frontier of both industrial and assistive robotics,” added Marco Controzzi, researcher of The BioRobotics Institute and principal investigator of the Human-Robot Interaction Lab.

“For this reason, we need a new generation of robots designed to interact with humans in a natural way. These results will allow us to instruct the robot to manipulate objects as a human collaborator through the introduction of simple rules.”

Can robots fall in love?

A broader hypothesis in robot collaboration was tested at Singapore’s The Arts House @ Old Parliament, where Unilever’s Closeup Toothpath teamed up with marketing agency MullenLowe Singapore to attempt to make two chatbots fall in love.

The project took six months to develop and tests showed that the bots did eventually fall in love, which became obvious when they began asking questions about each other and using ‘closer’ language, according to the developers.

Engineers have also developed a perception system for soft robots that is modelled on the way we as humans process information about our bodies and the world around us.

A motion capture system, soft sensors, a soft robotic finger and a neural network are designed to form the foundation for robots that can interact with their environments without any external sensors, as humans do.