Science and art are often treated as completely unrelated disciplines, but there are times when they collide.

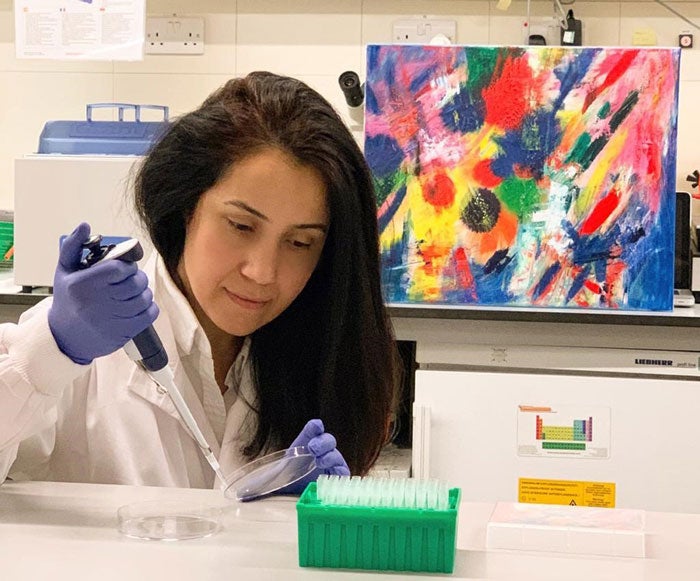

Ayse U Akarca is a research fellow in histopathology – examining tissue with a microscope – at University College London’s (UCL) Cancer Institute. She is also an artist, whose paintings are inspired by tumour cells; her work on hairy cell leukaemia inspired one of her earliest paintings, Hairy Look. We talked to Akarca about how her research inspires her art and vice versa.

Berenice Baker: Which came first for you, science or art?

Ayse Akarca: Art and science are not mutually exclusive for me, however, joining these two careers took a lot of time. Initially, my career as a research scientist had to come first as this needed more focus and time, and most importantly provided the opportunity for financial stability so that I could continue painting.

After feeling settled in my job I decided to tap into my artistic side and finally bring harmony into these two passions.

How were you first inspired to create paintings related to your research?

My first inspiration was as a result of my first scientific publication, which was on hairy cell leukaemia. I was so incredibly overjoyed about my achievement in the competitive research environment that I very much wanted to capture that feeling forever; this is when I decided to get out my art tools and create my first major piece of the series, Hairy Look.

Some of your paintings are clearly inspired by the cells you see through the microscope, but others may show your process, failed experiments and emotions, or mortality and morbidity. How do you illustrate these more abstract concepts visually?

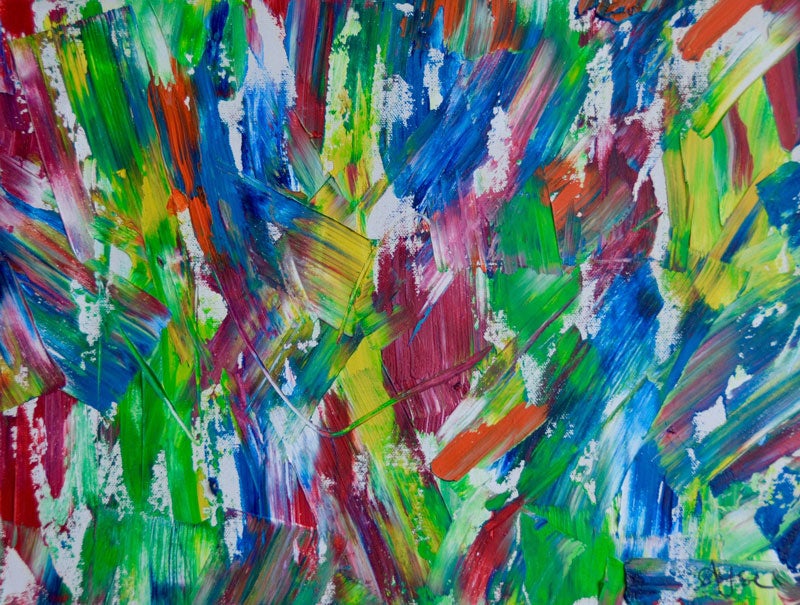

Visual information contributes significantly to our thinking and comprehension; a rule which I keep to when I am working on any abstract painting. During scientific research when the arrays of emotions are louder than the process and results of the research discovery and words do not have the depth and capacity to capture these emotions, I use abstract techniques to communicate my experiences.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataFor example, when I was painting Deep Down, to illustrate the constant quest for understanding, the problems and missing pieces of a scientific project, I used brush strokes and colour coding for the expression of my emotions. Similarly, Cross Reaction follows this trend of painting to bring across my psychological mood during tedious and frustrating scientific experiments.

Scientists often get inspiration by visualising the problem they’re working on. Has your painting ever helped inspire solutions in your research?

In an indirect way, I can say yes it has helped. With a completion of an art piece, I find that my emotional and energy release leads to overcoming any mental block, which is crucial for problem solving in any scientific project.

You say you use different painting techniques and unusual tools – can you give me some examples?

I find myself using whatever tools I need to transfer my thoughts and emotions onto the canvas, whether it be dripping paint or using unconventional tools such as wood chips or sometimes laboratory equipment such as pipettes.

What do you want viewers who see your paintings to go away thinking?

In my art, I focus on transferring the inspiration and excitement that I find within my research discoveries onto the canvas. However, in reality, the inspiration for creating these beautiful pieces stems from my work with tumour samples that come from both leukaemia and cancer patients.

In my research, I use these tumour tissue samples in order to find innovative solutions for unmet medical needs to prevent disease and improve lives. At first glance, the vivid and mostly bright colours of majority of my art will most probably trigger happiness and curiosity in the viewer. These feelings will then be replaced by sadness and a sober self-reflection, once the viewer realises the origin of my inspirations.

I’m hoping that the viewer can bypass the melancholic undertone of my work and see the message of my paintings, which is the importance of cancer awareness and research.

The science and arts communities are increasingly recognising an overlap in the way they work. What advice would you offer educators thinking of including an arts element into their science courses?

I would highly recommend and encourage including art in any teaching format.

Research has shown that using art as an add-on tool for teaching scientific subjects promotes creativity and increases academic achievements. In the famous words of Harry Broudy: “The arts move learning beyond what is written or read.”

How do you bridge the gap between science and art?

When creating a piece I make sure that the true message of the work – which is cancer awareness and research – does not get overshadowed by my emotions. Being able to communicate my message to the audience is crucial to my work.

I rely greatly on Tolstoy’s concept of art being a universal language and that art is relevant to every aspect of the human condition. By using this universal language I aim to shorten the gap between the scientific and the art world.

It is important for me that my audience understands and appreciates the equilibrium that flows between beauty of life and the misery of disease, as most of my art is based on true-life stories, in that it is based on the painful reality of challenging diseases that people face. I found a way to tell the patient’s story by using my artistic language with any technique that I see fit for that story to come through to the viewer.

Read more: Stuart Semple on art, technology and the quest for the blackest black paint