As globalisation has continued its steady expansion, competition for foreign direct investment (FDI) has also intensified across the world. Meanwhile, FDI has climbed up the priority list of governments over the past few decades, meaning countries are increasingly making moves to review their policies in a bid to attract investment from multinational companies.

A tool commonly used to sway would-be investors is investment incentives, which are designed to attract investors to host countries by offering them a mutually beneficial arrangement.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

What is an investment incentive?

Incentives are often used to stimulate FDI and can hold more value than the capital committed initially, with longer-term benefits including raised employment, exports and tax revenue. They can also be used to boost specific sectors of interest for the host country, with the foreign investor frequently offering benefits such as training, local sourcing, improvements in research and development, and building up the target sector’s presence.

Investment incentives are typically offered by government bodies at national, regional and, in some cases, local level. Mark Williams, the president of site location and incentive negotiation firm Strategic Development Group (SDG), explains: “[Incentives] started to become popular as development agencies began to ramp up [their activities] after the Second World War. The purpose of an incentive is to influence someone’s decision related to site location – i.e. induce them to do something that a community, country or state wants them to do. Incentives are offered – particularly in the US – by local governments, regional governments, states, electric utilities, railroads, gas suppliers, and so on.”

Alex Ash, global director of location strategies and incentives at Hickey & Associates – a global site selection, credits and incentives advisory firm – explains how varied incentives can be: “[Investment incentives] can take the form of capital expenditure, or some kind of value such as intellectual property creation, something that generates value in the form of tax receipts, financial investment or job creation in that jurisdiction. So it’s kind of like a quid pro quo. If you – being the target country – help me the investor fund my investment, I will invest in your location.”

The search for a definition

There is no single definition of what qualifies as an investment incentive; however, they typically fit into one of three categories – financial, fiscal or ‘other’ (including regulatory) incentives.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData• Financial incentives are more directly connected to cash flow and typically include a form of grant or loan that usually helps alleviate the upfront costs of investing. These tend to be favoured by developed countries and economies in transition.

• Fiscal incentives are connected to some sort of tax break such as tax holidays or reduced tax rates. However, these can often have an expiry date attached. They tend to be favoured by developing economies, and are often connected to free-trade zones, where regulations may not be subject to the same level of scrutiny.

• The ‘other’ category covers the broadest range of incentives and can cover areas such as subsidised infrastructure, regulatory concessions and more ‘soft’ creative incentives.

Commonly used investment incentives

Below are the most common types of investment incentives deployed by governments, which are mostly financial and fiscal.

• Investment grants, loans and subsidised government insurance. These forms of low-to-no interest loans can sometimes exceed 50% of the investment costs and are usually implemented to help save on the initial set-up costs of new projects. They are a good way to give instant gratification to an investor. However, they have been criticised for taking money from taxpayers to give to foreign entities in the short term.

• Discounted land, relocation and expatriation. Another form of subsidy that is not directly monetary is land or real estate offered at a reduced price, or in some cases for free. Some governments also offer help with capital costs for businesses that have relocated their operations, including assistance with moving workers and their families.

• Reduced tax and tariffs. There are many ways in which tax breaks can come into play when considering different types of investment incentives. Reduced corporate income tax, tax holidays, concessionary tax rates, accelerated depreciation allowances, duty drawbacks and exemptions can all be implemented for set periods of time. Tariffs on imports and exports can be removed or reduced, which could allow for large long-term savings, particularly in sectors such as food and drink, automotive and manufacturing.

This can bleed into special economic zones, also known as export-processing zones, which many developing economies are already implementing, areas that adhere to different economic regulations to other parts of the host country. For investment incentives, countries can create a tax-privileged zone, which is a similar concept, where the corporate tax rate is lowered for a specific sector or certain companies depending on what that government is trying to attract.

Creative thinking

Although the above are the most typically implemented incentives, Ash at Hickey & Associates highlights that there is room for creativity and negotiation when incorporating incentives.

“Some locations get very creative and some are less creative,” he says. “Some of these softer incentives can also be very valuable.”

Williams at SDG agrees that being inventive when negotiating incentives can be effective.

“Communities and states should be thinking about the incentives that won’t cost them much but are really valuable to the investor in affecting their location decision,” he says. “Some cultures like to have roads named after their companies, which is not an expensive endeavour, but it can have great meaning. Everything doesn’t have to be currency-rich and costly.”

Further examples of the more creative investment incentives are:

• Infrastructure subsidies. These are usually implemented in order to increase the accessibility and attractiveness of a site or general area. This can include building roads, railways or harbours that are designed to aid the investor’s needs.

• Training workforces. If a foreign investment brings a new type of operation to the host country, there could be potential issues around sourcing a qualified workforce. By committing to educational training programmes, governments can boost the number of qualified workers in the area.

• Administrative support. The host country, perhaps through an investment promotion agency, may assist with the required paperwork to help alleviate the many tasks required when locating somewhere new. This could include filling out paperwork, advising on visa programmes, securing preferential treatment from regulatory authorities and speeding up processes.

• Initial wage subsidies. For a limited time, the host country can assist with covering parts of the investor’s workforce wages to help with initial costs.

• Investing back. Sometimes governments will take a longer-term approach to investing back into the new project in order to have the power to influence business decisions. These can take the form of marketing strategies and bigger-picture operating plans. This can be done in the form of a direct investment to the company or, more indirectly, in the form of goods and services.

When dealing with investment incentives, negotiations are key to the conversation from both the investor’s and the host country’s perspective.

Ash also stresses the importance of keeping the long-term picture in mind.

“What you want in any negotiation is a conversation where you align the interests of both parties,” he says. “You are creating a long-term relationship with the local ecosystem and community. You want to make sure that the incentive discussions are entered into in good faith with a view of developing long-lasting relationships. That might also mean that you are less hard-nosed.”

How have investment incentives evolved?

Since the second half of the 1980s, FDI has been expanding at a rapid rate on a global level. Alongside this, investment incentives have diversified and become intensely competitive, particularly between competing locations that have a commonality, be it economic or geographic.

This shift to more intense competition often blurs the difference between incentives intended to promote FDI and other policies and regulations that relate to the retention of capital. A common criticism of incentives is that they tend to be most attractive – and therefore successful – in a neoliberal environment that thrives on low regulation and taxation. This, critics claim, can sabotage economies in the long term and create a race to the bottom between countries implementing aggressive incentives. Therefore, policies that are based upon the regulation of incentives are crucial to every country.

Williams explains that this has seen incentives and their objectives evolve.

“If you look at a 50-year period, [incentives have] become more prominent and utilised more often,” he says. “Incentives were often based primarily on job creation and what has happened over the past 50 years is that they have become more capital intensive, meaning that much more money is invested per job created. As a result, job creation has become less relative to the amount of money spent.”

Williams clarifies how this has affected investment in the US particularly.

“[In the US], another part of the evolution of incentives is looking at the risks that are taken by entities offering incentives and how states and regions mitigate those risks. For example, if we give something to someone, how do we know they are going to perform? What are the drawbacks? What can give us reliability in that sense? How can the public be guaranteed performance will occur?” he says.

Investment incentives at their core are a tool used by governments to convince investors to pick their location. Williams covers a few of the most helpful incentives for site selectors to consider:

“[For site selection] what we are doing is running a financial analysis,” he explains. “We do a discounted cash flow analysis and it appears to be that what is available earlier is worth a whole lot more than what is available later. Inducements that are available earlier are most important: the inducements that are closest to cash and usable and that are not complex. This is because there isn’t a lot of risk involved.”

How are they regulated?

Regulation related to incentives differs widely across the globe, with countries that operate under tighter rules frequently critical of those that are liberal in handing out incentives.

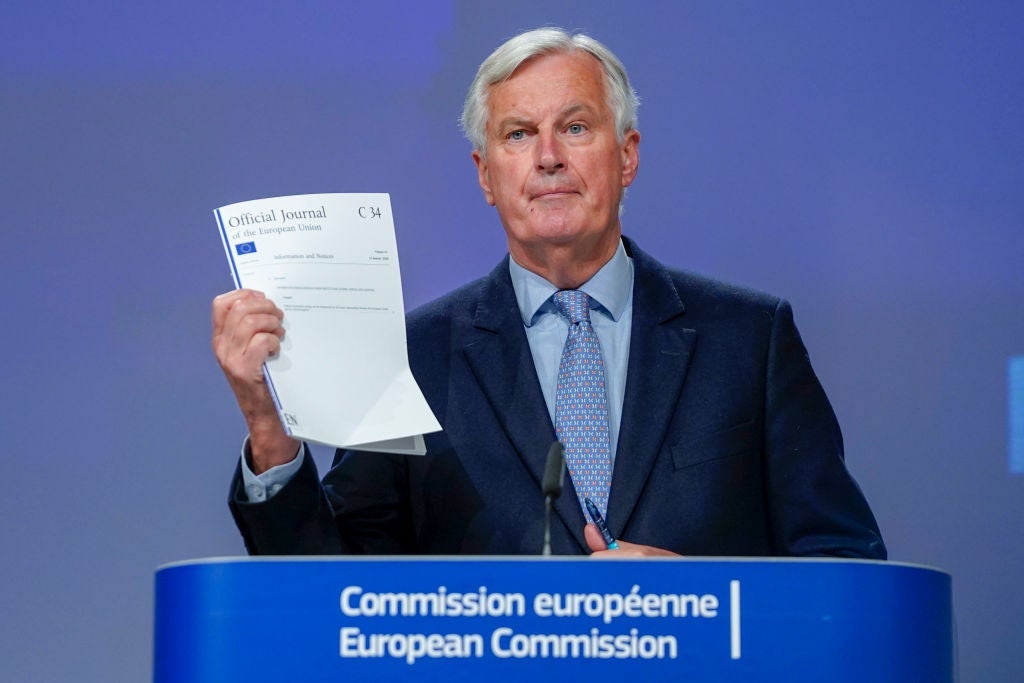

The EU state aid regime is considered to be one of the more heavily regulated bodies in the world when it comes to dealing with investment incentives. This has created a fairly level playing field for EU member countries and helps to avoid bidding wars between them for investment. It also incorporates special rules that help pull investment to low-income countries and low-income regions within member countries. This framework, however, is limited to EU member states, which means that when the UK leaves the EU, it will have the ability to negotiate independent incentive packages, potentially unlevelling the playing field.

Ash explains: “State aid is absolutely central to the Brexit divorce settlement and is one of its most contentious issues. The intention [of the EU] is to try and maintain a level playing field that doesn’t distort the market. The fear is that the UK will be free to do what it wants and that level playing field will go away.”

This shows how important regulation is over incentives to maintain economic balance.

Outside of the EU, regulations are much more limited, or in some cases non-existent. There is a network of international investment treaties that aim to make it easier for companies to move their operations across borders. However, they tend not to include restrictions that prevent countries from making moves to ‘outbid’ each other for investment, adding to the competitive pressure surrounding investment incentives.

There are also a relatively small number of agreements that do contain rules that prevent countries from lowering or failing to enforce their labour or environmental laws, in a bid to attract or maintain investment. However, there is arguably a lot more work still to be done on a global scale to create more equal regulations on the use of investment incentives.

The US, in particular, sees the use of regulations vary from state to state, which can create inward competition for investment.

Williams explains: “In the US, there are a couple of variables related to the types of incentives and the vigour of incentives. There are some parts of the US that are more vigorous and more aggressive than others. The south-east, for example, is somewhat aggressive; the north-east, not so much.”

On the theme of aggressive incentives, Williams continues: “After the 2008 recession, states, regions and localities were typically very aggressive in incentive offers because they were trying to redevelop their economies. I expect we are going to go through another cycle and I have seen this probably three or four times in my career, where there will be more of an aggressive and innovative approach, until such time as full employment or satisfaction in that regard occurs.”

These cycles, which work in correlation with recessions or times of crisis, have created different strategies around the implementation of incentives.

Williams says: “It is an art and a science. We have models that calculate incentives, calculate risk, calculate timing, calculate net present value, and it makes the ability to negotiate more important.”

Ultimately, incentives can be implemented as a tool to help countries pursue their development strategies. They can help to correct dwindling markets and boost business environments alongside a whole host of operational benefits to sectors.

On the other hand, the competition that results from loosely regulated incentives can divert financial resources that could have been put towards other development purposes. The value of an investment brought in by an incentive can also be called into question or diminish over time, meaning that the resources put in to acquire the investment could end up being a waste of government resources.