Director and producer Gary Sinyor is something of a black sheep in terms of British independent cinema.

Unlike most indie films, he doesn’t much go in for experimental film or aspire to great personal art. Instead, Gary’s focus is commercial independent film.

His most noted films have mostly been broad comedies.

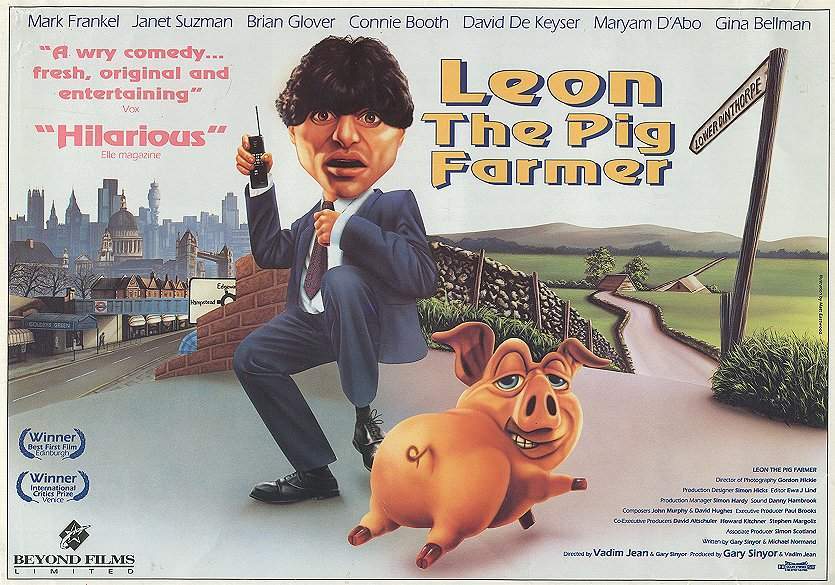

Leon The Pig Farmer, which brought him critical acclaim (winning the FIPRESCI International Critics’ Prize at the 1992 Venice Film Festival) was about an Jewish estate agent learning late in life of a artificial insemination snafu meaning his biological father was not the popular local businessman he grew up with, but a Yorkshire Dales pig farmer.

Sinyor followed this critically acclaimed film with Stiff Upper Lips, a parody of British period drama, and The Bachelor, a rom-com with Renée Zellweger (which was also Mariah Carey’s acting debut!) The BAFTA nominated director has very different aspirations for his films compared to most indie directors.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataAfter I question whether independent film can pick up the slack from a disappointing slate of big-budget box-office hits this year, Sinyor sighs. It’s unlikely, he suggests, precisely because most independent films are more interested in critics than audiences.

“I think most independent films are made because people are looking at Oscars and awards and something like that. So it’s like “we’ll do an independent film, we’ll release it in December, and we’ll get awards for it.

“And these are intelligent films. And it’s like, great, we’ve gone to see an intelligent film. But I don’t think the expectation for them to do that $120m with an independent film, that’s also commercial… you know, independent films tend to be, you know “we’re independent and we’re artistic, and we’re aimed at the east coast and the west coast and we’re not really going for middle America.”

So why does he approach his films in this way? By way of explanation, he offers a story of Paul Brooks, who produced Leon The Pig Farmer:

“He smashed it in America because he made a film called My Big Fat Greek Wedding. The distributors said ‘we’ll put it on five screens’ or whatever but he had faith in it. He believed in, and he nurtured, and he made sure it was released in a particular market, and it built and it built and it built. It was extraordinary. I was actually living there at the time. It was taking $10m and it ultimately built up to $120m or something…

“And it’s unusual to find a film that actually does that. A film that is independent and it plays beyond the east and west coast and into middle America.

“I think the independent films are made for Los Angeles and New York and Chicago, the big cities and don’t really have reach beyond this.”

Sinyor’s real focus is to create films that build. Leon The Pig Farmer, he explains, was one of those films. It’s obviously a point of real pride for Sinyor that his film started small and went on to win some huge awards, but it could all have gone a very different way.

When the film was due for release in 1992, most cinemas absolutely refused to play it. However, the Everyman in Hampstead took a chance on the feature which set the ball rolling:

“We ended up breaking the box office record at the Everyman in Hampstead which we still hold. And then it opened in six cinemas, then it went to twenty, then it went to twenty-eight, then it went to fifty.”

However, this is a rare case, Sinyor explains, especially in the 21st Century. The cinema industry nowadays, he says, is more focused on the short-term gain; films that smash the box office on their opening weekend then are swiftly put out to pasture as time goes by.

“Now there are so many, I’ll call them blockbusters, but I mean wannabe blockbusters, coming out of Hollywood. Especially Marvel films, of the comic book genre, each one with a budget of $200m and they play for two weeks and they’re gone and then another shows up two weeks later. Films are just coming and going a lot faster. People go to see them on the first weekend, they get their target audience, and then the drop-off rate is substantial.

It’s just almost impossible to get the cinema space because there’s always another big film coming along and the big film dominates…

“There are more films than there are cinemas, in all honesty. All films want to be shown in cinemas, so the cinemas get their pick.

“The other fact about this is that cinemas get programmed by people with very specific tastes. So you tend to see a certain type of British film. If it’s a period drama, they’ll say ‘oh, there we go, that’s our period drama audience’, and check that box, and they programme it. There are specific types of films that the people who programme, who control the British film industry, are used to taking.”

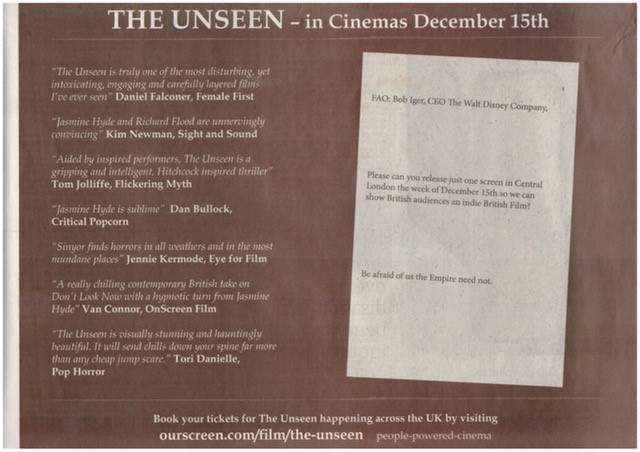

This is something of a sore point for Sinyor. Just last week he made headlines (literally) after taking out a page advert in the Guardian where he asked Disney for a favour.

In advance of their upcoming Star Wars film, Disney has locked up cinema space in all of central London for the week of 15th December. This means Sinyor’s new film The Unseen can’t find a cinema space.

Unfortunately, that’s the same day Sinyor’s new film, The Unseen will be released. Sinyor’s ad, addressed to Disney CEO Bob Iger begged the corporation to release one cinema space to play The Unseen.

“We’re not under any illusions that we’re in any battle with Star Wars. Clearly we’re not. We’re a British independent film that seems to be getting very good reviews and therefore we’d like to get to an audience and build on that audience. The only way we can do that is to get a screen.

“So really this is an appeal to Disney to release us a 50-seater cinema somewhere in central London which would have very little effect on them but it would enable our potential audience to go and see the film. And then it might open in another cinema and so on and so forth.”

Of course, knowing that Star Wars had locked down a release date for The Last Jedi by January 2016, I wondered why on earth Sinyor had picked that day to release his own film in the first place. It turns out that it was a clever marketing trick that has gone a bit wrong…

“We chose that date for a number of reasons. I think mainly it was a deliberate policy to think ‘everyone is going to avoid Star Wars like the plague’. If you look at any other week of release at any other time of the year, twenty-odd films are being released and if you look at December 15th, there are about five. And that’s because no big film wants to go against Star Wars…

“So for a little film, it actually made perfect sense… the newspaper editors can only give so much space to Star Wars. They can’t dedicate their whole review section to Star Wars. So as opposed to having, 19 other films we might have been in competition with any other week, we’ve only got four! So hopefully we will get more space. And that was the plan.

“When you’ve got very little budget, what you rely on is, the reviews and word-of-mouth. It was a question of getting space which we thought we’d get in the broadsheets as well as the tabloids. So it was actually a deliberate policy that’s backfired.”

Seeing as The Unseen is predominantly set in the Lake District, Sinyor even attempted to get cinema space there. Unfortunately it was not to be. In fact, the closest cinemas available to the Lake District were in Preston. When I mentioned that I was from Preston myself and had never seen a full cinema there in my life, Sinyor sounds angry:

“I mean, that’s also interesting! You go to a cinema and you go see a film that seems to be doing well and you go on like the second Saturday and it’s only half full or 40% full!”

This leads us to the topic of Justice League which, after taking just under $94m on its opening weekend was derided as a failure. After two weeks, it has actually just about broken even. But Sinyor laments the lack of interest in seeing films grow.

“It’s extraordinary! It was released on the Friday afternoon, and I saw something on Facebook, the projections went down from $180m to $95m. And $95m doesn’t sound too bad, but for them it’s a disaster. Because $95m drops off by the next weekend. It’ll drop off by 50%. So then exponentially you can track it. If it’s going to take $95m then it’ll take half of that the next weekend, then it drops off almost altogether.

“There’s almost this equation now which is ‘everything is going downhill after the weekend’. Which wasn’t the case and doesn’t have to be the case. When I made Leon The Pig Farmer. We went into more cinemas mostly because of word of mouth. And I think something similar happened with The King’s Speech which started small and then it built. Those opportunities are probably there for independent films, but it’s a fight.”

Of course, Sinyor’s major concern isn’t just that films like Justice League take up cinema space undeservedly, but that they take up media space too:

“The thing that’s interesting, for me, is that you get a film like Justice League (I’m not the target audience for it at all) but it’s getting really bad reviews. Two star reviews, pretty much consistently. And it’s getting not just the space but the editorial space. The big film reviewers, their main review for that week was Justice League – Two Stars. And they could have used that space to focus on other films and giving them the promotion. The films that they’re going to give four stars to, give those the promotion and put Justice League in a little box. Pick a film that you like, and give that the promotion. But that’s not how it works because the studios have a lot of power.”

So what is the solution to this crisis? How can independent films ensure that they find their audience? For Sinyor, the answer lies with the BBC:

“I am absolutely convinced that the way for the British independent cinema industry to really thrive and have a major impact is for the BBC to be forced, literally forced, to show 52 independent films per year, one a week on a Sunday night, that they have had nothing to do with.

“They show a film a week at 10 o’clock at night on a Sunday, that would be British film time. That would radically increase the number of actors who are known to British audiences and would increase the amount of imaginative writing that would come out. It wouldn’t be either ‘let’s do a gangster film’ or ‘let’s do a period drama’. You’d get actually innovative writing. You’d get a range of films…

“[The BBC] haven’t been involved in development or casting or anything. They should be forced to buy, for very little money, because let’s say you’ve bought a film for £100,000, that programming would cost them 5 times that to buy something else or to make something…

“We pay the license fee! Stop showing whatever rubbish you’re showing on Sunday at 10 o’clock and show British independent films… It would ensure that 52 films are being made every year. If you’re an independent filmmaker like me, I’d be able to make The Unseen again if, chances are, the BBC will buy it and view it. That would make a huge difference. The viewing figures for BBC Two are 3 or 4 million. You immediately increase your pool of film stars. After a few years you’d end up with thirty or forty people who are film stars that help the British film industry into the next era.

“That is the way forward. It should happen. It should literally just happen.”

Verdict reached out to BBC Films for comment but did not get a response.

So what about Gary Sinyor’s own film? The director is critical of British independent film being pigeon-holed as period dramas or crime movies, but what is his film about. Well, he explains, it’s a commercial independent film. That is to say Sinyor is aiming towards a mainstream audience with his film.

“It’s a psychological thriller about a woman who believes she’s responsible for the accidental death of a child. She and her husband begin to react very differently. Her husband begins to think he can hear the voice of a child from his bedroom and she starts to have panic attacks which make her go temporarily blind.

“And when she goes temporarily blind, the audience also goes temporarily blind, so it’s a real kind of visceral experience with her. So these two characters who are completely fucked up are basically offered the chance to get away to a retreat in the Lake District by a guy who they stumble on. He says ‘you’ve suffered enough so come along to my, y’know, gaffe, if you like and nest up’. And they go there and things don’t get any better, I think it’s safe to say.

“I mean, it’s got a lot of twists and turns. One of the things I really love about it is that its go so many twists and turns that people in the audience, their imaginations, they’re thinking ‘hold on, what’s going on?’ all the time. They’re trying to work out what’s going on. And I leave to their imaginations to see if they can guess it and see if they can work out what’s going on.”

For any director, that’s must be an incredibly gratifying experience, I suggest. Sinyor’s excitement and pride is palpable. He tells me that those reactions are the type of thing directors can only get in cinemas.

This is why he’s so passionate about getting cinema space. A lot of effort went into the sound design, he tells me, which is best heard on cinema speakers. He tells me that he worries that once The Unseen is released on home media, the audience’s reception may be very different.

There’s something about sitting in the dark with a huge screen and big speakers that just can’t be replicated at home.

Early reviews of The Unseen have compared the film to works by acclaimed director Alfred Hitchcock. I wondered whether this was an intentional influence though Sinyor assures me that’s not the case:

“I was always aware that the possibility of being compared to Hitchcock might come about, simply because it’s a psychological thriller, which in itself people go ‘oh sounds like Hitchcock’, especially if you’re British. But also it’s not really about money and drugs. When people think about thrillers they think of car chases, money, and drugs… And this is not (like those.) There’s no money in, there’s no drugs in it, it’s really about people. It’s much more like Girl On The Train or that sort of thing. It’s just not something we’ve done in the UK, as far as I can remember, for quite a long time.

“But my influences were more like Don’t Look Now or Sixth Sense and those references have come out… I think someone called it a chilling, contemporary take on Don’t Look Now. Well, you know, I’ll take that any day of the week.

“But yeah, I understand it. We did use source music from Hitchcock films to use as guide music. Because Hitchcock was brilliant with music… So the composer Jim Barnes was kind of aware that what he was doing was kind of emulating Hitchcock music.”

Interestingly, the filming of The Unseen was all done in sequence. Essentially, that means scenes were filmed in order. Normally this isn’t the case. In most films, shots taking place in the same location are all filmed back-to-back. This normally results in movies being filmed out of sequence.

“I wanted to shoot it in sequence so that the character motivation for the actors was easy to know where they were, it was easy to know where they were in the script. Given that there were a lot of twists and stuff it really made sense to shoot as much of it in sequence as possible.”

Creatively, Sinyor explains, filming The Unseen was the best few weeks of his life. That’s because the cast of three and crew of eight all lived together in the house they filmed in.

“We’d get up in the morning, go down and have breakfast, and then we’d start filming. So there was no travel, getting into vans or going out to a location, we were literally there.

“It was very focused, I guess. We had a great cast. I mean, Jasmine Hyde’s performance is being lauded and rightly so and Richard (Flood) and Simon (Cotton) are both really incredible in it also. So it was a joy, a complete joy. It was literally the best four weeks of my life creatively and it was the best shoot I’ve ever been on. The crew were fantastic. I mean, we were a small crew and we lived in this house and everyone go on very well.

“Considering the material is quite dark, it was a very good working ethos. A couple of nights we worked later because we were shooting stuff at night, but mainly we were using natural light so at about 6 o’clock it got dark and we stopped and made dinner. It was reasonably civilised.”

From the audiences who’ve seen it so far, the response to the film has been incredible, says Sinyor. When I suggest that this might be the perfect picture for film fans who aren’t interested in Star Wars, he strikes a more conciliatory tone.

“Well, I mean, there are themes in common. Like family and loss. And Star Wars does do that quite well, I think. They do the son-daughter parental thing, they do that reasonably well considering what it is: a big blockbuster event film. The last film had Harrison Ford and Carrie Fisher caring about their son, and the son killing the father, y’know, it’s interesting. They try a little bit to be slightly more intelligent which is okay.

“But we’re a much deeper and quite an emotional experience. I think it is an experience. I’ve seen the film in the cinema with audiences and I’ve never heard an audience so bloody quiet? People won’t go to the toilet and they won’t cough because they’re so tense about what might be happening or not. So it seems to be like an experience where people are rooted to their seats, and that’s obviously what I was going for.”