Graphene layers were only first successfully extracted from graphite in 2004, but chances are graphene is already in your mobile phone, car, tennis racquet or the wings of an aircraft you’ve flow in. But its full potential is only just being imagined.

Such is the interest in graphene that at a recent lecture in Modena, Italy, so many people attended a public lecture by physicist Professor Sir Konstantin “Kostya” Novoselov, who with Andre Geim earned a Nobel Prize for his work on graphene in 2010, they spilt out of the venue and onto the street.

Two days later, international packaging innovator Tetra Pak held an open day at its Modena R&D facility to celebrate joining the Graphene Flagship, the EU’s biggest scientific research project with a budget of €1bn, where Novoselov told Verdict that graphene began as a side project.

“Andrei Geim introduced style of work in our lab that from time to time we’d do something completely different outside of the of our normal field of interest,” he explains. “Andrei is known for frog levitation, but graphene was one of those side projects. So the question was, can we make transistors out of graphite.

“When we started that project, I knew for sure that graphene shouldn’t exist but you can at least try to make the transistor. We almost gave up. And then we found the way how to make thin layers of graphite and starting to work with those and it took us about a year before we realised that we can make graphene.”

Graphene is a near-transparent single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal grid, with a range of important properties including high strength at low weight, excellent heat and electricity conductivity, and the ability to act as a barrier or selective filter.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataWhile commercial applications are only in their infancy, Novoselov says that like all novel materials, establishing manufacturing processes and ensuring health and environmental safety take time, so for it to have penetrated markets so far in just 15 years is a good result.

“I think it’s time to give the steering wheel to the companies rather than to the academics”

Novoselov is chairman of the Strategic Advisory Council of the Graphene Flagship, a body which he believes has been critical to graphene’s research journey to date, but he says it now needs to shift away from academia.

“I think it’s time to give the steering wheel to the companies rather than to the academics and in the second phase of the organisation we need to work with them much more closely so they can tell us which direction to go,” he says.

Novoselov says Tetra Pak is one such innovative company looking to disrupt in materials, production and technology to make the most of graphene’s potential for the packaging industry. And Tetra Pak vice president for programme management and managing director for the Modena site Sara de Simoni has been instrumental to its introduction.

“We started looking into graphene in a more serious way one year ago when we started a future talent programme with [development engineer] Gloria Guidetti,” she says. “She has a PhD in a graphene technology so we started to speak with her about graphene’s potential. She suggested Tetra Pak should join the Graphene Flagship.

“Tetra Pak has this trend of being very good in incremental innovation; I’m really excited because when it comes to disruptive innovation, graphene might enable smart digital packaging.”

How graphene could enable digital packaging

Digital packaging incorporates flexible electronics and printable sensors that make interacting with packaging intuitive for customers. It is just one of three potential paths for disruption in the industry. The second is the packing material itself, where graphene could provide a lining barrier that would provide the same waterproof property as plastic but could, for example, selectively allow certain gases to escape but still be fully recyclable.

“Then for the last area, I go back to my dear equipment,” says de Simoni. “We struggle with quality issues on our equipment because the environment it works in is pretty aggressive and we have to do deal with issues very fast for customers. So I see new materials making them more robust and less exposed to the aggressiveness of the environment and to operator error at little additional expense.”

But Novoselov says that the timescale for the wider adoption of graphene is subject to the ‘hype cycle’.

“Ten years ago we thought that graphene will never get into applications, and then seven years ago we were starting to believe that everything was going to be made out of graphene. The reality is somewhere in between” he says.

And while headline-grabbing applications such as flexible mobiles phones that users can roll up and put in their pockets are still some years away, graphene is gradually getting into our daily lives in ways we don’t even notice.

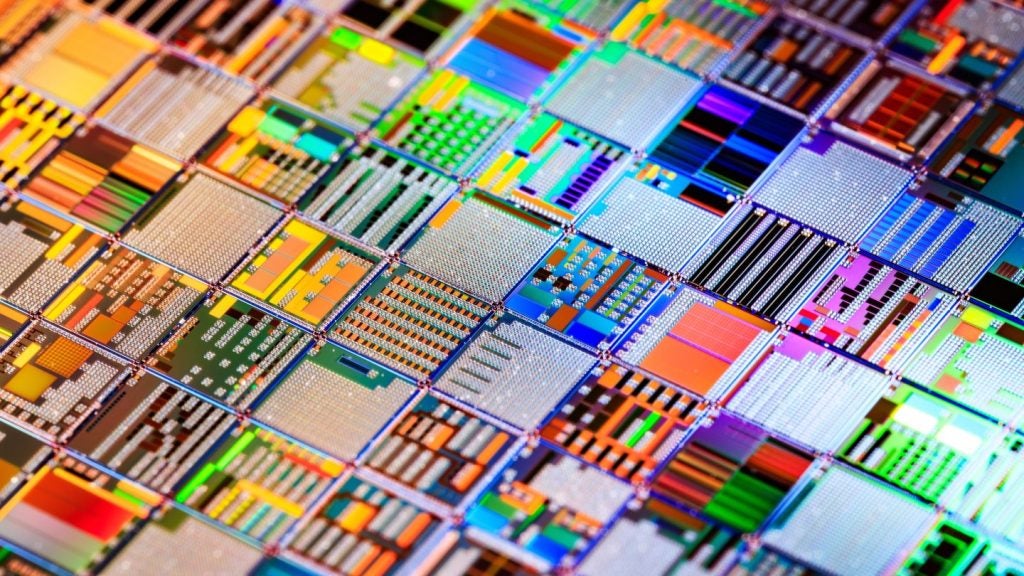

“Our phones have graphene in, most new Ford cars have graphene parts,” says Novoselov. “For me, it is a signature of maturity that the material gets into our lives without being noticed. It just naturally takes a long time to introduce any new material. Even a new microprocessor takes two or three months to develop, depending on the complexity.”

Graphene’S Holy Grail

Novoselov’s Holy Grail for graphene is for it to be used in disruptive applications where it doesn’t simply add another property or replace another material just because it does the job a little bit better.

“I’m really looking for applications which are created by graphene which were not possible before or started to be available only because of graphene,” he says. “There are some of those on the horizon, but I don’t think we’ve seen them yet.”

Novoselov identifies graphene’s potential use as a membrane as one of these. It would enable water purification processes to filter out chemicals and drugs that enter the water supply that current processes struggle with, for example.

“Graphene is the thinnest possible material; it’s only one atom thick so it’s a perfect membrane, and you can make it impermeable or permeable to certain atomic species,” he says. “That’s the opportunity, the capability which we’ve never had before, so I think using graphene as a smart membrane for various technologies would be quite interesting.

Read more: Made for walking: Testing the world’s first graphene hiking boots