Chinese telecoms titan Huawei announced that it plans to invest $100m in startup support in the Asia-Pacific region to use its cloud software. While the move shows the company’s endeavour to become Asia’s top cloud provider, it also highlights China aim to expand its international digital power.

The announcement was made at Huawei’s Cloud Spark Founders Summit, which took place simultaneously in Singapore and Hong Kong on Tuesday. The company said that the Spark Programme in the Asia Pacific region aims to build “a sustainable startup ecosystem for the region over the next three years.”

Huawei wants to recruit a total of 1,000 startups into its Spark accelerator programme and shape 100 of them into scaleups.

“Through this programme, we are working with local governments, leading incubators, well-known VC firms and top universities to build support platforms for startups in many regions,” said Zhang Ping’an, CEO of Huawei’s Cloud Business Unit. “Now 40 startups are participating in our programme.”

Zhang added that Huawei has launched its “Cloud-plus-Cloud Collaboration and Joint Innovation Programme”, through which it will support startups with $40m worth of resources and support 200 startups in the Huawei Mobile services ecosystem.

Huawei’s up against it

The news comes after Huawei was crippled by US sanctions due to its links with the Beijing government. Since it was slammed with the Trump era sanctions, the company has been looking beyond its smartphone business and searching for ways to boost its revenue from software services.

Huawei has been on an aggressive hiring spree in recent months. The tech giant is recruiting experts and PhD candidates with expertise in artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, autonomous vehicle engineering, software and computing infrastructure, chip development and quantum computing.

In recent years, Huawei has been rapidly expanding its cloud business.

“We are looking to become a top-three cloud services provider in the Asia-Pacific in the next three years,” Zeng Xingyun, president of Huawei Cloud operations in the region, told the South China Morning Post this week.

Simultaneously, rival Xiaomi has also been making headlines recently. After experiencing 83% year-on-year growth during the second quarter in 2021, the electronics company has achieved a 17% market share for smartphones, surpassing Apple to take the number two spot in the global smartphone market.

Last year, the company’s CFO, Chew Shouzi, voiced the company’s goal to become a global player.

“We expect that in the next few years, we’re going to continue to invest in our international expansion in western Europe and also across the rest of the markets,” he said.

Xiaomi can boast that it’s kept its promise, as the company took the top spot in Europe for smartphone sales in 2021, with 12.7 million phones shipped in the second quarter.

A new digital world order

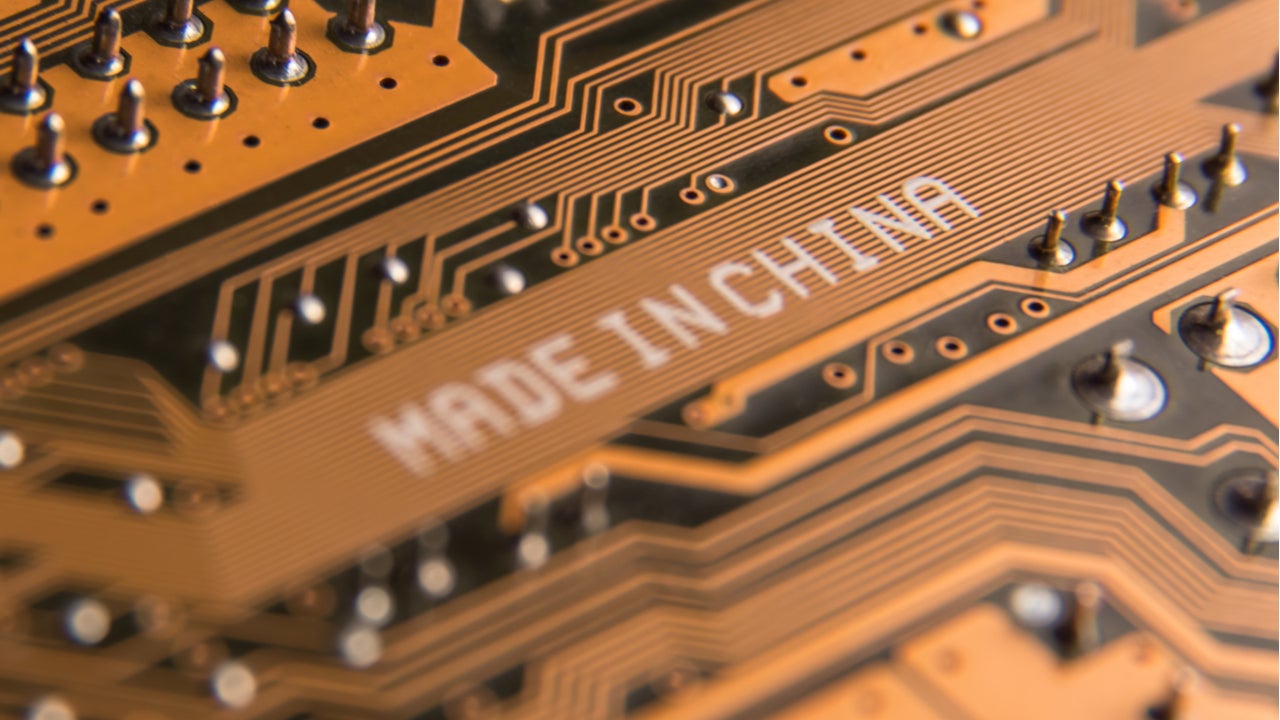

However, there is more going on. To understand the bigger picture, one needs to zoom out and look at China’s long-term plan to lead the world into global connectivity with its Digital Silk Road (DSR) initiative.

Launched in 2015, the DSR is part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s strategy to grow its power internationally. Like the BRI, the digital arm is not monolithic and involves many actors at all levels across the public and private sector. As a result, companies such as Huawei and Xiaomi are an essential part of the larger plan.

China’s digital expansion worldwide – notably in Africa, parts of Asia, Eurasia, the Middle East, South America and certain countries in Europe (e.g. Serbia, Poland and Hungary) – is led by big tech companies.

The DSR aims to improve digital connectivity in participating countries, with China as the main driver of the process. On the macro level, the DSR is about the development and interoperability of critical digital infrastructures such as terrestrial and submarine data cables, 5G cellular networks, data storage centres, and global satellite navigation systems.

“’Team China’ has filled ‘digital voids’ in frontier markets, enhanced digital infrastructures in emerging markets and in some more advanced economies, with its lead in 4G and 5G telecoms as a major factor,” explains Michael Orme, senior analyst and China specialist at GlobalData.

China’s DSR project is about much more than just infrastructure. At its core, the DSR is a solution that engenders a less US-centric and more Sino-centric global digital order. President Xi Jinping is pursuing this goal by enabling the opening of new markets for Chinese tech giants such as Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei, and by strengthening the world’s digital connectivity with the Middle Kingdom.

Xi’s goal is to reduce the country’s vulnerable dependence on other tech-leading nations, such as Japan, a few selected European states and, most importantly, the US. The DSR aids Chinese tech giants and smaller players to boost their sales and local know-how and gain a foothold in overseas markets – often with the help of Chinese government policy facilitation.

Orme explains that, over the last decade, Beijing has sought to protect its global supply chains and its overland and maritime trade roots from Asia to Europe – while building markets and a Chinese presence en route – via port, road and railway projects.

“At base, China is in the process of building a global economic and security zone around itself what it insists is for its survival and increased autonomy, which is as independent as possible from US technology and influence,” he adds.

Recent projects thus hint towards Beijing’s goal to become self-sufficient. For instance, China recently completed the launch of its global satellite system, BeiDou, which, in some regions, is more accurate than the US global positioning system (GPS).

In a move to create its own blockchain network, China is pushing ahead with its digital yuan, making it the first country in the world with a state-backed cryptocurrency. Beijing’s push to implement a state-backed digital currency can be seen as a move to take back control over the economy and to weed out private sector and foreign cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and ethereum.

Some say safe, others say surveillance

Much of this expansion is based on what the Chinese call “safe city” technology, which includes AI loaded surveillance technology from companies such as SenseTime and Hikvision.

Some see China’s expansion as a boon for developing countries, while others worry that Beijing’s growing cloud poses a threat to freedom and democracy.

Moreover, the Covid-19 pandemic has given some regimes the excuse to buy Chinese “safe city” technology which is much cheaper and more available than what the US and Europe can and are prepared to offer via companies such as IBM, GE, Cisco, Ericsson and Siemens.

“There is an unhealthy appetite in the world for China’s panoptic technology,” Orme says.

Leaders of many developing countries have signed deals with China that form a part of the DSR. Although these agreements are not legally binding, in many cases, they show the scope of global interest in technology made in China.

“In short, China has filled a global vacuum left by the West,” Orme argues.

As a result, some democracies have raised serious concerns about China’s DSR push. They worry that, at a time when Beijing is becoming more assertive globally, China will use this technology to enable recipient countries to adopt its model of technology-enabled authoritarianism.

As the standoff between China and western countries continues, we can expect developments in the tech industry to become even more polarised.

Much of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan is about achieving Chinese self-sufficiency. However, “unlike the US, which could be an autarky as it is, China is far from self-sufficient. It can’t feed itself and has to import a lot of oil and semiconductors,” Orme emphasises.

An issue that Beijing is well aware of which explains its ambitious goal to become fully self-sufficient in the semiconductor market by 2035.