There was once a time when unicorns – privately held startups valued at over $1bn – were almost as rare as their mythical namesake. But now there is a new rare breed catching the attention of investors that some argue is more suitable: the decacorn.

When venture capitalist Aileen Lee coined the term unicorn in 2013, there were just 39 companies that met the criteria. Her analysis showed that of the software startups founded in the 2000s, just 0.07% of them reached a $1bn valuation. Unicorns were genuinely hard to find. As such, hitting the vaunted milestone was usually an indication of a startup with high promise.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

But data shows the term – at least under its original definition – might be out of date.

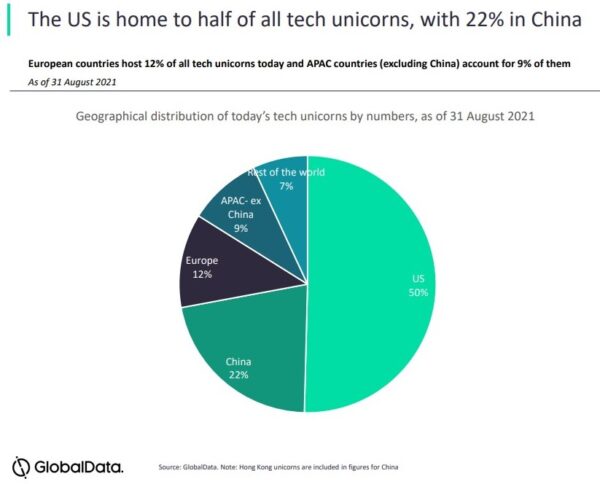

There are 826 unicorns worldwide, as of 31 August 2021, according to GlobalData’s thematic research. That’s a twenty-onefold increase since 2013 and represents a 46.5% compound annual growth rate.

In other words, unicorns have multiplied to such an extent that it is hard to justify calling them rare.

By comparison the number of decacorns – privately held companies valued at $10bn or more – remain just as elusive as unicorns were back in 2013, with GlobalData research showing there are currently 35 roaming the world’s startup ecosystems.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“With startup investment now much more accessible and commonplace, there is an argument that [the unicorn] milestone is no longer as significant when identifying rare startups,” Rakesh Narayana, global director of new ventures at Reckitt, tells Verdict. “Just as the world of investment has evolved, so do its benchmarks and in 2021, decacorn is perhaps a better way to signal maturity for a company.”

Why are there so many unicorns?

Ballooning levels of venture capital investments over the past decade have played a key role in unicorn creation. These capital injections have inflated the valuations of companies, driven by an insatiable investor appetite for companies laced with just a whiff of tech.

This is borne out by GlobalData’s figures: of the 826 unicorns today, 751 are classed as technology companies.

“Investors are keen to back these tech unicorns as many have flourishing business models and increasing customers,” says Swati Verma, associate project manager of thematic research at GlobalData and author of its report on unicorns. “This also explains why we see a large number of unicorns operating in ecommerce, cloud and fintech.”

The first half of 2021 saw record levels of global venture capital investments, according to Refinitiv data. Global venture capital funds invested $268.7bn to the end of June – outstripping the $251.2bn invested throughout the whole of 2020, which was itself a record-breaking year despite the pandemic.

Startups are also reaching unicorn status at a faster pace. In 2018, research found it took an average of seven years from launch to reach the milestone, with 19 startups reaching $1bn in less than a year.

While there are comparatively far more unicorns today than a decade ago, some investors point out that unicorns are still rare compared to the total number of startups.

“If you compare the total number of unicorns to the total number of tech startups that have been founded during the same time period, the percentage of startups that actually made it to unicorn status is still very low,” Mathias Ockenfels, general partner at Speedinvest tells Verdict.

He puts the current percentage of unicorns to total startups at less than 1% of all tech startups.

“Hence, from a founder's perspective it is still very hard and somewhat unlikely to build a unicorn,” he adds. “From an investor's point of view, it remains extremely hard to find and invest into a future unicorn.”

The US is home to half of today’s unicorns, while China is host to nearly a quarter. Despite the dominance of these two countries, more unicorns are popping up in disparate places. According to Verma, the replication of similar business models across multiple geographies has helped drive the rise in tech unicorns.

“After Uber's success, Ola Cabs in India and Grab in Singapore also received strong funding, turning them into unicorns as well,” she explains.

An investor frenzy and highly scalable, easily replicable business models have helped to create herds of unicorns. And based on current trends it shows no sign of slowing down: there were 228 new tech unicorns created in the first half of 2021, according to GlobalData’s research.

This will continue to make unicorns less rare, all while contributing to the rise of the decacorn.

Who are the decacorn startups and what sectors are they in?

This year has been the year of the decacorn. Almost a third of the decacorns that exist today reached that status in the first half of 2021. Startups are also reaching decacorn status at a faster pace.

But which companies are decacorns and what sectors are they in?

The list of unicorns is heavily dominated by ecommerce, cloud and fintech startups. Decacorns follow the same trend.

Fintech is the most common theme for decacorns, accounting for nine of the 35 startups to have passed the $10bn valuation milestone.

They include London-based digital banking and payments startup Revolut, which as of 31 August had a valuation of $33bn, making it the UK’s most valuable startup.

Revolut’s valuation is trumped by Swedish buy now, pay later firm Klarna at $45.6bn. But the highest fintech valuation goes to Stripe at $95bn.

Ecommerce is the next most common theme for decacorns, with five startups making up the ranks. Among them are $39bn Instacart, $15bn GoPuff and $14.3bn Grab.

The third most common theme is cloud, with three decacorns including $11bn Celonis, $10bn TalkDesk and $10bn Gusto.

Elon Musk’s rocket company SpaceX has revolutionised commercial space travel and, in the process, reached an out-of-this-world $74bn valuation. Other estimates put this figure closer to $100bn.

And the most valuable private tech company? That’s Chinese internet company and TikTok creator ByteDance, with GlobalData putting its valuation at $140bn as of 31 August. Some estimates put that figure as high as $250bn or a staggering $400bn, demonstrating the opaqueness and guesswork at play in startup valuations.

Decacorn alumni include ride-hailing giant Uber and short-term home rental firm Airbnb. Their IPOs crystalised then-valuations of $82.4bn and $47bn, respectively. Neither company is yet to report an annual profit.

Is the term unicorn still useful?

With unicorns on the rise and decacorns the new rare breed, does the term still have value in the startup and scaleup ecosystem? Or will investors start looking at decacorns as the new prize breed?

Harry Briggs, managing partner at OMERS Ventures, says that it’s still an “amazing milestone to build a business valued at $1bn” and it can help companies attract talent.

However, he points out that in a “world where we’re seeing valuations as high as 50x or even 100x revenues, the valuation doesn’t necessarily represent as great a business achievement as it did when valuations were more conservative”.

He adds: “I’m afraid I can’t take the word decacorn seriously – an animal with ten horns sounds more of a curse than a goal.”

Verma believes there could be a gradual shift towards focusing more on decacorns, but that doesn’t mean the term unicorn should be dismissed entirely as it could mean missing trends.

“Unicorns are now not just restricted to developed countries,” she explains. “We are seeing an increasing number of unicorns even in Africa. Also, we are seeing the emergence of unicorns in buzzing themes such as ESG. So, I think the term unicorn is still fit for conducting research.”

While it has become more common for a company to reach unicorn status, it still maintains a level of prestige that is sought by founders and investors.

“A unicorn remains hard to build – and if you want to become a decacorn, you first need to pass unicorn status!” says Speedinvest’s Ockenfels.

Private company valuations are a useful metric to measure progress and inform a potential investment. Unlike public valuations, the process isn’t straightforward or transparent and much of it is based on assumptions and estimates, with valuations often shared publicly following a funding round.

As such, reaching unicorn status is often a chance for founders to promote their company and separate themselves from the crowd.

It is for this reason that Verma believes becoming a unicorn will “continue to be an ambitious benchmark for tech startups”.

But others think the term has little relevance in the business world.

“It’s common to have some investors exclusively work with unicorns and with the rise of decacorns, we may well experience a similar preference,” Sarah Barber, CEO at Jenson Funding Partners, tells Verdict. “But the reality is that both of these may be a bit misleading. While a startup being classified as a unicorn is a fantastic achievement, for many it may be an unrealistic target.”

She points out that there are plenty of startups that don’t reach unicorn status but are still worthy of investment and can still create a “successful, sustainable revenue-generating business” that creates jobs and introduces innovation.

In Europe, for example, there are an estimated 22.6 million small and medium-sized enterprises that play a vital role in the economy.

Others have suggested using the term "dragon" to describe a company with a private valuation of $12bn or more net of venture funding.

Some go further and argue that the terms unicorn and decacorns are merely semantics.

“Decacorns, unicorns, it’s all just PR bluster and it’s time that we moved on,” Toby Harper, founder of law firm Harper James and former VC tells Verdict. “What really matters is that entrepreneurs and their investors are building businesses that make a profit and contribute to the future of their industry or, more broadly, society.”

He adds: “Everyone wins if we focus on backing and celebrating those successful businesses rather than constantly looking to wax lyrical about megacorns or googlcorns.”