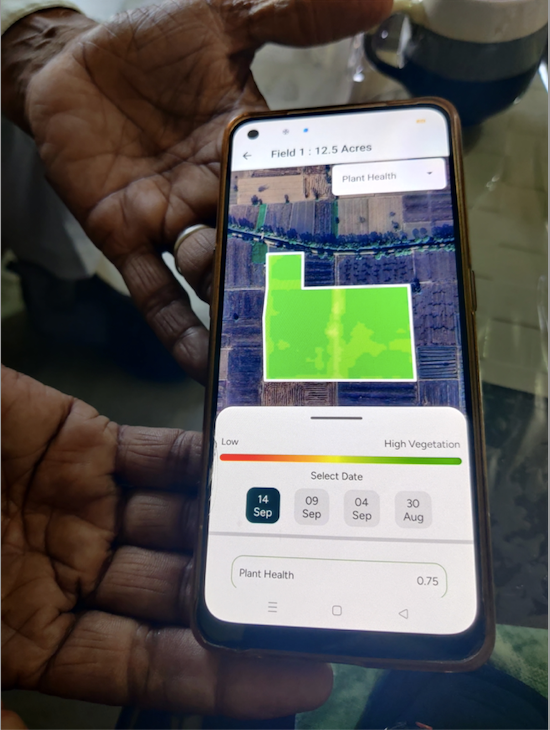

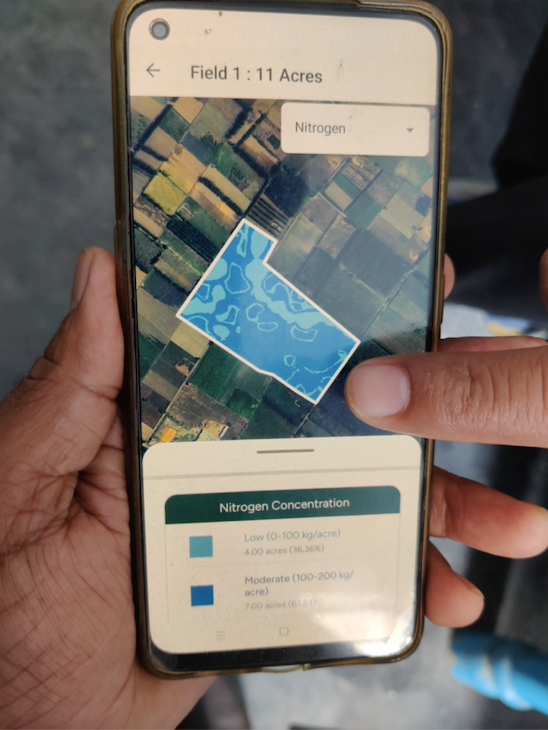

Dalip Ram, a rice farmer in the north Indian state of Haryana, inspects an app on his smart phone showing a satellite map of his farm. This app is the product of a San Francisco-based tech company called Boomitra that uses data about the farmer’s land to calculate how much carbon he is managing to lock into the soil of his small plot in order to generate carbon credits. Boomitra just won the Earthshot Prize – which seeks out “the most innovative solutions to the world’s top environmental challenges” – in the ‘Fix Our Climate’ category.

Hundreds of thousands of farmers like Ram are being targeted by tech companies that aim to help them generate and sell soil carbon credits. According to research by soil scientist Jon Sanderman at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts, US, 110 billion tonnes of carbon have been released from the top layer of soil by agricultural activities over the past 12,000 years. Now, companies, farmers and policymakers are wondering: can we put it back?

In Haryana, there are farmers implementing new farming practices to improve soil health and increase soil carbon sequestration. For example, they are no longer burning stubble (the plant stalks left after harvest) but instead using it to create mulch, which nourishes the next crop and sequesters carbon in the ground. Boomitra has teamed up with local organisations to implement such ‘regenerative’ farming methods. According to the terms set by Verra, the world’s leading certifier of carbon offset credits, farmers must implement at least one additional regenerative practice for their carbon credits to be approved.

Boomitra is one of a growing number of companies focused on soil carbon sequestration. Its soil carbon projects in India and elsewhere await final approval by Verra, but it is already working with farmers across five million acres of farmland globally. In India, Boomitra has enrolled 100,000 farmers across 300,000-plus acres of land, and presold several tens of millions of dollars’ worth of soil carbon credits to companies looking to cut their carbon footprint. Once Boomitra’s projects are fully up and running, revenue will flow both to the company and the farmers and partners with whom it is working.

Boomitra’s CEO and founder Aadith Moorthy is excited by the huge growth potential in India. The company has enrolled just 0.1% of farmers so far. “Over the course of the next six months we will probably make that several 100,000,” he told Energy Monitor.

“It is a gold rush,” says Srajesh Gupta, co-founder of the Centre for Grower-centric Eco-value Mechanisms (C-GEM), an initiative in India to develop farmer-centric carbon markets based on natural farming. Companies including Indigo Ag, Nori and Soil Capital are hurrying to sign up as many farmers as possible to decade-long contracts, before the competition heats up. Boomitra hopes it can convince farmers to stay engaged over several contracts, implementing more and more changes on their farms.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData“You start with the very simple stuff like composting, mulching,” says Moorthy. “Then you go to more complicated stuff. For every set of practices, there will come a time when you exhaust the amount you can increase soil carbon by; then you must go to the next [set of practices].”

Ram, who farms three tracts of land across 25 acres in Haryana, is in a ten-year contract with Boomitra. It can take several years before a change in farming practices raises the soil carbon level so longer contracts make sense. Boomitra will encourage Ram to keep renewing his contract but, if and when he chooses to leave – or stops for another reason – the company will have to monitor the soil of his land for 100 years, according to the rules set by Verra. Depending on what happens, Boomitra may have to compensate for so-called “reversals” (carbon that was stored and sold as carbon credits but then released).

When Ram enrolled with Boomitra, he created a profile of his farm on the company’s app, including proof that he is the registered owner. Roughly every month, he and other farmers must upload data about their farming practices to the app; in return they receive regular updates about the condition of their land, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and moisture levels.

Boomitra combines the “ground truth data” it receives from farmers with information from multispectral satellites to create artificial intelligence (AI) models that work out what is happening in the ground and how much carbon is being sequestered. Boomitra says it has taken upwards of one million soil samples to construct “a robust dataset, which allows for the creation of regional soil models across the globe with accuracy, detail and scalability”. The AI models calculate likely changes in soil quality and carbon levels.

Are soil carbon credits reliable?

However, is the science of soil carbon sequestration reliable? Can we measure soil carbon changes with sufficient accuracy? Verra itself has come under fire for ‘phantom credits’. More fundamentally, are the agri-tech companies behind these schemes gaining access to valuable data via a back door? Jaskiran Warrik of the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Food Innovation Hub in India is supporting companies like Boomitra to find partners, but she concedes there are a lot of unknowns.

“There are some things that science is still figuring out and we don’t have consensus on,” Warrik says. ” For example… if you are really sequestering carbon in the soil, is it having the kind of impact that you want it to have? There are varying studies and there isn’t enough information.”

According to Sanderman, the scientific research available gives a positive view of the potential for soil carbon sequestration in agricultural soils. “We know we have run down the amount of organic carbon in most agricultural soils; this creates an opportunity to rebuild that depleted soil carbon stock and remove CO₂ from the atmosphere in the process.”

However, management and measurement of soil carbon is a challenge, he admits. Farms have to implement specific management practices for many decades to maintain carbon sequestration, Sanderman says, which is especially hard for small farmers to do.

It is impossible to detect change at the individual field level cost effectively, so many companies in this space, including Boomitra, Indigo Ag and Regrow, use AI modelling to estimate carbon sequestration, aggregating data from thousands of fields. There are different mechanisms to handle the statistical uncertainty in modelling of this kind. Verra’s recommendation – VM0042 – was developed by Indigo Ag and Terra carbon, both soil carbon companies themselves. However, they work primarily with North American farmers, who farm large tracts of land, so the mechanism is ill-suited to measuring soil carbon sequestration across multiple small farms.

In the end, models are a less than perfect way of getting round the prohibitive cost of direct measurement. Sanderman says: “The models seem to do a decent and conservative job of representing average change within [certain] conditions, but they are basically flying blind when moving outside of their limited training space.”

None of the eight farmers or two local organisational partners Energy Monitor spoke to for this story have yet received payments from Boomitra but the company claims that farmers will receive 55% of each carbon credit sold (where one carbon credit equates to around 1.1 tonnes of sequestered carbon, taking into account a ‘buffer pool‘). The current market price per credit is between $15 and $25 and Boomitra estimates that, depending on crop type and geography, farmers should be able to sequester an average of 1–2 tonnes of carbon per acre per year.

Going forward, the financial gains for commercial farmers could be significant but, even if carbon prices go up over time, the profits for small farmers will always be small. A farmer like Ram could expect to earn upwards of $400 from carbon credits in a year, based on current prices and how effectively he manages to improve carbon sequestration.

Nevertheless, given the precariousness of many farmers in India, even a small extra revenue stream could be useful. Ram says he is saving money thanks to Boomitra’s app, which gives him useful information and advice based on the data he uploads. For example, with real-time data about his land, and regular updates on moisture levels, nutrient deficiencies and crop growth, he can optimise his use of fertilisers. He says that even if the soil carbon credit money never comes, this is a service worth having.

Energy Monitor spoke to several Indian farmer organisations that have been approached by Boomitra. They said they were intrigued by Boomitra’s proposition. Soumya Dutta, an Indian environmentalist, told Energy Monitor: “If you don’t look at who is funding a company like Boomitra, what they are proposing seems a very natural solution. Boomitra’s proposal appears to support better agro-ecological farming, which will hold more carbon in the soil, which will help in tackling climate change.”

The digitisation of agriculture

In the end though, Dutta and several NGOs Energy Monitor spoke to for this story are unconvinced by the company’s mission statement. They point out that Boomitra has partnered with oil company Chevron and Yara, one of the world’s biggest fertiliser companies.

Dutta is concerned that apps such as Boomitra’s offer a direct route for companies like Yara to sell to farmers. Federico Ronca from the WEF is working with tech companies and agribusinesses to promote digital innovation in agriculture. He says Yara is interested in using the “services and metrics Boomitra can generate”.

Boomitra’s website states: “Yara partners with farmers in East Africa to improve land management and provide quality solutions, from inputs to mechanisation. With Boomitra, Yara motivates farmers to adopt sustainable practices through carbon finance, and uses Boomitra’s technology for precision agriculture advice.” In other words, Yara uses Boomitra’s analysis of soil conditions to advise farmers, as well as earning carbon credit revenue. Yara did not respond to a request for comment.

Some of the world’s biggest agribusinesses are using such a business model. “A lot of agribusinesses, including Bayer, Corteva, BASF and Syngenta, are acquiring or partnering with satellite data companies, data analytics companies and drone companies in order to sell integrated products which will tell farmers how to farm,” says Kavya Chowdhry, who works for ETC Group, a small, international collective that monitors the impact of emerging technologies and corporate strategies on biodiversity, agriculture and human rights. A 2022 ETC report, Food Barons, called a lot of the partnerships between agricultural and technology companies “very opaque in terms of data sharing”.

India’s Government is actively promoting the use of digital technologies in agriculture and, in the process, partnering with some of the world’s biggest tech companies. “The [Indian] government has already signed some 14 MOUs [memorandums of understanding] with big companies including Amazon and Microsoft,” says Chowdhry. Microsoft is developing a platform called Agri Stack to be used by Indian farmers to upload data. India’s Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers’ Welfare says on its website this will “make it easier for farmers to get access to cheaper credit, higher-quality farm inputs, localized and specific advice, and more informed and convenient access to markets”.

However, a recent blog post by GRAIN, an international non-profit representing small farmers, argues that Agri Stack “will effectively open the gates for the technology company (Microsoft) to access vast troves of information, including personal data and details of farm conditions”.

According to Rohin Garg, an independent researcher, “rural India may not be completely ready for the large-scale digitisation of agriculture and it creates the potential for huge injustice in terms of who profits from farmers’ data”. Some farmers have access to digital technology, but most small and marginal farmers (89.4% of agricultural households in India) likely do not. Another problem is consent: farmers don’t always understand what they are signing up for when, for example, they enter a contract with Boomitra.

GRAIN points out that the MOUs agreed by the Indian Government were signed before any data protection measures were in place. “This means that those who have the ability to collect the data become its owners, and those who have the capacity to process it get the first-mover advantage on the collected data,” it says. Meanwhile, digital technology advocates like Warrik argue that the challenges of data regulation should not mean we stop digitalising: “You really have to build the car while you drive it – and you just have to hope that it works,” she says.

Apart from the US company Indigo Ag, which issued its first soil carbon credits in June 2022 and February 2023, no carbon credits from soil carbon sequestration have yet been verified. However, Boomitra is optimistic that its Mexican project will receive Verra approval very soon, followed by projects in India, Kenya, Argentina and East Africa. As the Earthshot climate category winner, the company will get tailored support and £1m to do its part to “repair and regenerate our planet”.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on Energy Monitor and was funded by a grant from Clean Energy Wire