Ian Farquhar is the global field CTO and also heads up the security architecture team at Gigamon. The network visibility and traffic monitoring technology vendor was founded in 2004. It went public less than a decade later on the New York Stock Exchange in 2013. Elliot Management Corp acquired the firm in 2017 for $1.6bn.

Farquhar joined Gigamon eight years ago. He cut his teeth as Macquarie University’s Unix administrator when he studied there in the 1990s and served in a number of security roles before joining Gigamon, where he became field CTO in 2021.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

As someone who’s been emerged in the tech scene for the better part of three decades, he is prone to joking about things like the seven layers of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model, which describe how different computer systems communicate. These are usually referred to as the physical layer, the data link layer, the network layer, the transport layer, the session layer, the presentation layer and the application layer.

However, that also makes the Gigamon field CTO particularly well-placed to discuss trends in cybersecurity and how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has affected the sector. Those are both topics that we cover in this latest instalment of our series of CTO Talks where we also discuss the fun one can have with explosives.

Eric Johansson: Where did your interest in tech come from?

Ian Farquhar: I’ve always been fascinated by science and technology. I was one of those annoying kids who got as much fun pulling my toys apart to see how they worked, and I usually got them back together at the end. Sometimes, I even made them better. I remember my favorite toy as a kid was a Tandy (Radio Shack) electronics kit, where I strung together circuits using wires connected to little springs. I was also into amateur astronomy, which when I retire in a couple of decades, I plan to return to. So it rather runs deep in me.

What are the biggest mistakes people make when it comes to cybersecurity?

I think the biggest mistake is forgetting the human factors, which means more than just people. I often joke about the hidden OSI stack layers: 8 (the human), 9 (the organisation) and 10 (the legal and regulatory environment). When we don’t engineer for all these layers, we get bad outcomes.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataBut it’s not just looking at our users and rolling our eyes when they miss a phishing attack. As cybersecurity professionals, we need to look at ourselves, too. One thing I’ve noticed recently is how so many of us like to sit in our own comfort zones, and assume that’s good enough. We need to question ourselves more; challenge ourselves. You see this especially in zero trust, where people default to the familiar approaches: logging, agents, firewalls, endpoint. No, sorry, not good enough! The whole point of zero trust is to minimize the trust we place in things, and this is why those traditional solutions need to be enhanced by new approaches.

How do you think the current market uncertainties will affect the cybersecurity industry?

One of the challenges with cybersecurity is that success means nothing bad happens. This leads to a very legitimate question: if we hadn’t spent the money, would something bad have actually occurred? Logically, you’re being asked to prove a negative, and that’s inherently illogical.

Looking around the market, I see successful cybersecurity professionals taking control by focusing not only on what they prevent, but what they enable. In times of crisis, we need to be seen to be part of the solution. Many years ago, I was at a meeting of cybersecurity leaders, and a security manager for a bank shared this with me: our board wants to move into a new market. Legal says “we need a month”. Sales says “we can do it in three weeks”. Networking says “a month”. Infosec says “that’ll be six months for us”. We need to do better.

How do you think the war in Ukraine will affect the cybersecurity industry?

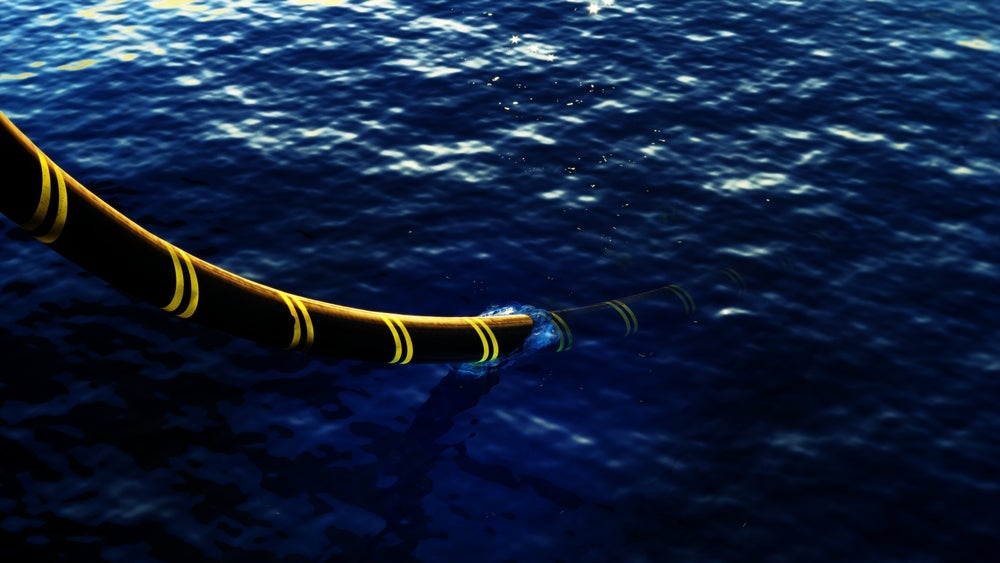

The Viasat hack has pushed the focus back onto attacks on embedded systems, as it should. We are surrounded by enterprise critical systems which aren’t traditional endpoints, servers and mobile devices. We need to protect them too, and “out of sight out of mind” is simply not an option.

What one piece of advice would you offer to other CTOs?

Focus on the infrastructure you really have, not the bits you’re most familiar and comfortable with.

What’s the most surprising thing about your job?

That I cannot recall a significant conversation with a fellow practitioner, where I have not learned something new. This is a diverse field, full of complexity and nuance. No matter how much you think you know, there is always something new to learn.

What’s the biggest technological challenge facing humanity?

Climate change. It’s an existential threat, and addressing it will influence almost every single aspect of our lives and the technologies which form a part of it. I firmly believe history will look at those changes as positive.

What’s the strangest thing you’ve ever done for fun?

I don’t know whether I should admit this or not, but I got qualified in the use of explosives. This was very early in my studies when I was doing some physics courses, but there was a heavy aspect of interest too. It is extremely formalized, there was a lot of rote learning (especially around the laws related to mining), but I will never forget the headache I got during the practical’s weekend when I thoughtlessly rubbed my nitroglycerine-covered hands across my forehead and my blood pressure dropped. It made me relieved to hear that this mistake is a rite-of-passage, and that everyone does this once, and learns never to do it again. That practical weekend also involved setting off over a ton of high explosive in a quarry, and watching a whole cliff face peel off and collapse, which was awe inspiring to see.

I’m sure it won’t shock you to hear that I don’t put this training on my resume. I found it puts people off, but I’ll admit it here, and note that I still have the course notes for this, all these years later.

What’s the most important thing happening in your field at the moment?

I’m going to nominate zero trust, which might sound like a lazy answer following an industry trend, so let me explain why it’s not.

When I’m asked why cybersecurity is so difficult, I explain that trust is hard. I don’t mean in the cyber-realm, I mean any trust, in any realm. Interpersonal trust is hard, as we all know. For years we’ve been making trust assumptions and optimizations, like one side of our firewall being trusted, and the other being untrusted. Or that a person who we deem trustable today, lives in some life cocoon and remains trustable indefinitely. Zero trust is the first serious proposal to move us away from these assumptions and optimizations, towards constantly assessed trust evaluation. That’s a really cool concept, John Kindervag deserves total credit for creating it, and I think it will make a huge difference. When it happens. It’s going to take a few years, but the journey will be worth it.

I look at zero trust as like Y2K. The common “wisdom” is that Y2K was a waste of money, because so little bad happened. This is in reverse: nothing happened because that money was spent. So much old code, legacy garbage, and old systems were cleaned out and upgraded, and we probably benefited hugely from that for a decade after due to increased productivity and capability. Zero trust will require some changes, but I am convinced those changes will not only bring immediate benefits, but set a foundation which will give us a similar long term benefit.

That is why I say zero trust.

In another life you’d be?

Before I went to university, I wanted to be a film director. I applied to the Australian Film, Television and Radio School for three years in my high school years, and didn’t even get to the first interview. What’s really funny is that I ended up working at the AFTRS a few years later, supporting their IT systems, and I realized that I would not have done well, and that they rejected me wisely. Even so, to this day, I love movies, and I still flex this muscle through a hobby doing CGI (Computer Generated Imagery). That was an interest I developed when working with SGI, and the consumer-level tools I use today to amuse myself are vastly better than anything professionals had back then.

GlobalData is the parent company of Verdict and its sister publications.