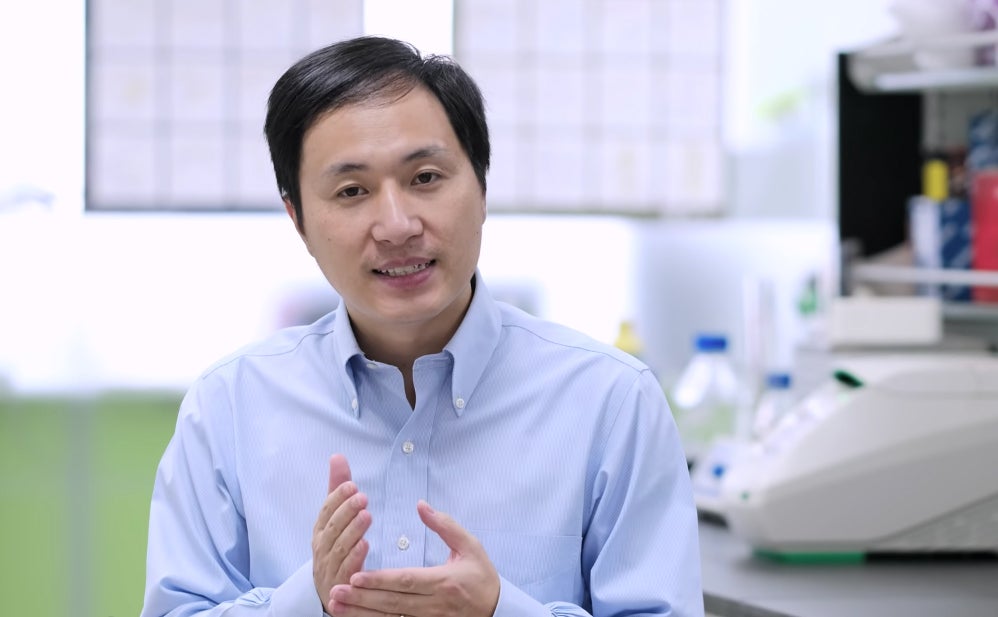

When Chinese scientist Jiankui He genetically modified twin babies in an attempt to make them immune to HIV last November, he earned worldwide condemnation from the scientific community.

Now, that same genetic mutation He tried to create has been associated with a 21% increase in mortality in later life, according to a study by the University of California, Berkeley.

He, a former associate professor and genomics researcher from Southern University of Science and Technology, genetically modified two human embryos in 2018 using a gene-editing technique known as CRISPR-Cas9 – a form of human germline engineering – to disable the CCR5 gene.

The CCR5 gene plays a vital role in allowing HIV to enter cells. By disabling it, He hoped the babies would be able to fend off HIV infection.

News of the world’s first CRISPR babies came during a press conference on 25 November. One of the twin baby girls reportedly has one copy of CCR5 disabled by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, while the other has both copies deactivated.

However, the CCR5 gene also defines other traits, leading UC Berkeley scientists to warn – based on their research – that people are “on average, worse off” for having the mutation that disables the CCR5 gene.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData“Beyond the many ethical issues involved with the CRISPR babies, the fact is that, right now, with current knowledge, it is still very dangerous to try to introduce mutations without knowing the full effect of what those mutations do,” said Rasmus Nielsen, a UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology.

“In this case, it is probably not a mutation that most people would want to have. You are actually, on average, worse off having it.”

CRISPR babies: “many uncertainties and unknowns effects”

The mutations that disable the protein and protects people against HIV infection naturally exists in around 11% of Northern Europeans. It is much rarer in Asians.

Researchers determined that there was an increase in later life mortality from the genetic alteration by scanning more than 400,000 genomes in a British medical database and comparing it to associated health records. The team found that those with naturally occurring mutated copies of the CCR5 gene had a “significantly higher” death rate between the ages of 41 and 78 than those with one or no copies.

In addition, the researchers said there were fewer people than expected with the two mutations in the database, indicating they are more likely to die before entering the database than the general population.

“Both the proportions before enrolment and the survivorship after enrolment tell the same story, which is that you have lower survivability or higher mortality if you have two copies of the mutation,” Nielsen said. “There is simply a deficiency of individuals with two copies.”

Postdoctoral fellow Xinzhu ‘April’ Wei highlighted the “uncertainties” that surround germline editing:

“Because one gene could affect multiple traits, and because, depending on the environment, the effects of a mutation could be quite different, I think there can be many uncertainties and unknown effects in any germline editing,” she said.

“CRISPR technology is far too dangerous to use right now”

The findings, published today in the journal Nature Medicine, are not the first study to highlight health risks with the mutated CCR5 gene.

Others have shown how people with the mutation are four times more likely to die after being infected by the flu. However, the Berkeley researchers say there could be multiple explanations for this because of the protein that CCR5 codes for is involved in many body functions.

“Here is a functional protein that we know has an effect in the organism, and it is well-conserved among many different species, so it is likely that a mutation that destroys the protein is, on average, not good for you,” said Nielsen. “Otherwise, evolutionary mechanisms would have destroyed that protein a long time ago.”

However, other studies have suggested that those with a naturally occurring CCR5 mutation may recover from strokes more quickly, as well as protection against smallpox and flaviviruses. It has also been shown to give an enhanced memory in mice.

“I think there are a lot of things that are unknown at the current stage about genes’ functions,” added Wei. “The CRISPR technology is far too dangerous to use right now for germline editing.”

Read more: The gene-edited baby scandal caused global shock. Now science is learning vital lessons