How good a representation of you is your data self? Do all copies of data have the same value? Artists are attempting to answer those questions with a bright pink robot, a digital pinball machine and an airport arrivals board at the Copy? That? installation at the Open Data Institute (ODI) in London.

The ODI is a non-profit founded by web inventor Sir Tim Berners-Lee and AI expert Sir Nigel Shadbolt in 2012 to advocate the use of open data for positive change. Copy? That? is the ODI’s research and partnership season for 2019 to 2020 seeking to question the trustworthiness of data as it gets repeatedly replicated across the internet.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

Evolution through errors

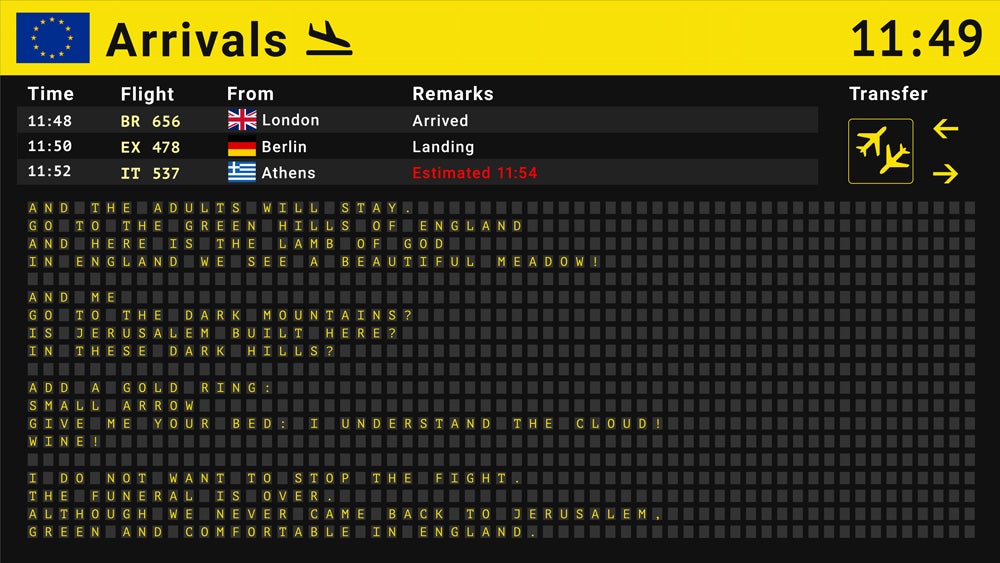

Poet Mr Gee explored the “soul of Brexit” with his installation Bring Me My Fire Truck. He took William Blake’s poem Jerusalem – often hailed as the unofficial English national anthem – and ran them through Google Translate for all 24 languages of the Europe Union (EU) then back into English. The results are displayed on an airport-style arrivals board with the place of origin indicating the language being translated. Bring Me My Fire Truck is the result of translating the line ‘Bring me my chariot of fire’ into German and back.

“The initial remit for the ODI has to do with copying and they asked ‘can a copy have the same value as the original?’” Mr Gee told Verdict.

“Being an artist, I know that copies and mistakes and flaws and discrepancies are what give birth to new art forms. So you could say that that rock and roll is a discrepancy from blues, and heavy metal is a discrepancy from rock and roll. As an artist, I embrace flaws and discrepancy.”

Mr Gee explains that his artwork uses an algorithm linked to Google Translate. It takes each of the 24 EU languages and translates the poem into that language, then back into English, then into that language then back again.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“What you have is a translation of a translation of a translation of a translation,” he says. “Each translation is portrayed as a plane arriving, so you’ve got a plane that is arriving in German, then it will arrive in English. And so then you will see the English version of the German translation.

“What’s interesting is as you stand and watch it, you start to see some lines have become funny, some become sinister all the meanings disappear and new meanings come into being. The words England and Jerusalem remain, so there’s always something to anchor you.”

Trusting technology with our data

The second piece, DoxBox trustbot, sees artist Alistair Gentry dressed as a, frankly disturbing, puppet-like character alongside a bright pink robot computer, whose cheery face and loud music encourages the audience to lean close to interact with it and hear what it is saying. Having gained the viewers’ trust, it asks what popular online platforms they use before shocking them with what personal data they have involuntarily shared.

“DoxBox is a pretend AI; it interviews you about your digital life and services you use, then it can tell you stories about the effect that might have on your life as a whole,” Gentry says in a video for the ODI.

“There’s a lot of real technology that’s pretending to be technology that is really just people behind the scenes. With this project, I wanted to make that plain. All of these systems, all of these apps have humans behind them and have human values embedded in them, prejudices that we have about each other; they’re all deeply embedded in the technology and the technology is not neutral.”

DoxBox’s pink, glittery and cute aesthetics, reminiscent of a Japanese vending machine, contrast with the fact that it talks about really dark things.

“In Japan, they’re particularly good at masking authoritarianism as cuteness, so the police force has a cute mascot,” says Gentry. “DoxBox is transactions; it’s coercive, it uses some of those dark patterns. It encourages you to share more than you might want to and it rewards you.”

Gentry says that, in contrast to these darker implications, the ODI helps ensure data can be free, fair, open and equitable, and that we could use the same technologies to genuinely do good and be nicer to each other, a positive side he also incorporates in his work.

“We live in the real world, obviously, but we also live in a world of data that surrounds us invisibly and has huge impact on how we live and the choices we have in our lives,” Gentry says. “I really hope that comes through in people’s interactions with DoxBox.”

Experiencing autism via pinball

Mood Pinball also reflects the more positive impact of the data that surrounds us. It is a digital pinball machine with custom software and graphics that attempts to communicate the experience of a neurodiverse individual exploring a city and the overwhelming noise therein.

Autistic artist Edie Jo Murray, Ben Neal and Harmeet Chagger-Khan created the artwork following a series of workshops for neurodiverse people at Birmingham Open Media.

Featuring dreamlike images in surreal colours, Mood Pinball sees players reimagine how city-wide data might be used by an individual to find their comfort zones, and improve their experience of a city. The goal of Mood Pinball is to keep its Mood-o-Meter at ‘happy’, by responding to noise-level data revealed by gameplay.

Read more: The science of art: How cancer cells inspired researcher’s emotive paintings