There are increasingly more countries with the so-called sugar tax around the world and today the UK’s sugar tax takes effect.

Over the past couple of years soft drinks in the UK have undergone major ingredients changes, shrinking pack sizes, and rising prices.

France took the plunge six years ago, whilst Norway has been at it for quite a bit longer — since 1922.

The levy might have its critics, but few will disagree that in terms of the global clampdown on sugar, the UK is well behind the curve.

The obvious question is whether or not it will work. The levy’s effectiveness in other countries is mixed; any long-term impact has depended largely on its implementation.

Each country has implemented the sugar tax differently.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataDifferent tax amounts, different sugar thresholds and different drinks criteria make comparisons between each country extremely tricky to make, but the consumption figures still tell enough of a story.

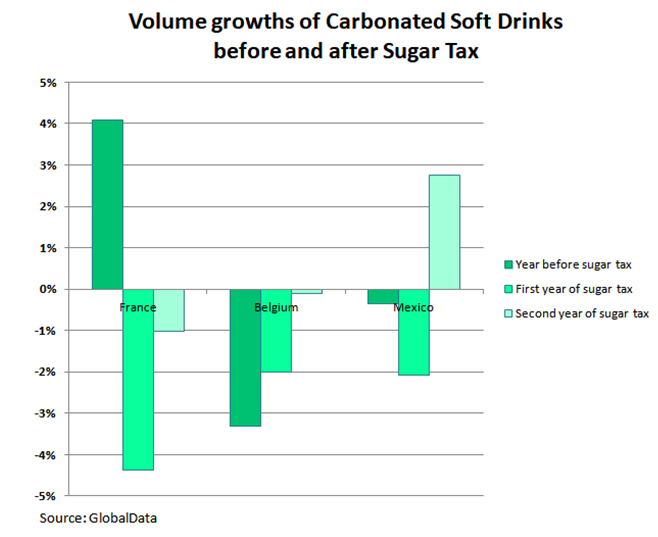

The below chart focuses solely on volumes in carbonated soft drinks, widely considered to be the main target of the sugar tax.

The sugar tax in France

Implemented in early 2012, France’s soda tax charged manufacturers the equivalent of an additional six pence per litre for any beverage containing added sugar or artificial sweeteners.

The tax’s primary objective was to push consumers towards healthier alternatives, and the impact of this was felt immediately. Carbonated drinks dipped for the first time in eight years, and the category has been in decline ever since.

Healthier areas of the market have performed admirably in recent years – particularly packaged water, for which consumption has risen by well over one billion litres since the implementation of the tax.

However, the French government was not fully satisfied, and in October last year it announced plans to raise the levy to a more significant 17 pence per litre for products containing 11g of sugar in every 100ml.

The sugar tax in Belgium

The no-nonsense approach to sugar prevention in Belgium promised much but delivered little.

The vast majority of soft drinks were hit by the 2016 levy, including those with only a minimal amount of added sugar. Critics were quick to question the need for the taxation at all; with carbonates volumes already falling due to widespread health concerns, their condemnation was understandable.

Even the healthiest of beverages were penalised by the slightest inclusion of sugar, meaning the incentive to avoid sweetened products was effectively lost.

Volumes of most drinks categories have been largely unaffected by the tax as a result. Carbonates’ annual declines are fractional at most, whilst the entire market’s performance remains highly dependent on the continued popularity of packaged water.

The sugar tax in Mexico

The taxation in Mexico had a rather surprising, albeit brief, impact on consumption volumes.

At an added cost of approximately five pence per litre, the levy triggered a 2% decline in consumption after 12 months. For a country which loves its sodas, that came as quite a shock.

Then, even more strangely, when consumers decided the price rises weren’t too steep, volumes surged back up to their highest point ever.

The implementation of the sugar tax in each of these three countries highlights the unlikely chance of a low tax amount having much long-term impact. With this in mind, the UK’s decision to roll out taxes of up to 24 pence on certain drinks looks like the right one.