The UK is ditching plans to give a tech regulator statutory powers, which experts warn could see Britain fall behind the EU which has just approved stronger antitrust laws.

British lawmakers are expected to shelve plans to bolster the Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA) Digital Markets Unit with stronger policing powers, according to people briefed on the situation speaking with the Financial Times.

The Digital Markets Unit was first announced in November 2020. The unit’s aim was to limit Big Tech titans’ ability to choke competition. It would work together with Ofcom and the Information Commissioner’s Office to achieve this goal.

However, now it seems that the Digital Markets Unit will not be granted statutory power, meaning it will not be backed by a law. The Queen’s Speech, which is due on 10 May, is not expected to include a bill backing the unit.

Julian Knight, Tory chair of the Commons digital, culture, media and sport committee, warned that the absence of a legislative push backing the new unit in the Queen’s Speech would “damage the credibility of the whole enterprise”.

“It would be a hammer blow to the capability of the UK to regulate these sectors,” Knight told the FT.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataUK could fall behind the EU in new tech policing

The news is a blow to the international efforts to reel in the power of Big Tech. Outside the UK, policy makers in the US, the EU and China have increasingly pursued these efforts over the past few years.

However, market experts now warn that the UK not giving the Digital Markets Unit could lead to the country falling behind other regions.

“The CMA has pledged in the past that it would use all its powers to challenge online practices that it think might harm consumers,” Laura Petrone, principal analyst at the thematic team at research firm GlobalData, tells Verdict. “But the problem is that without ad hoc legislation the CMA won’t be able to establish clear criteria defining prohibited behaviour – for example on using competitor’s data to gain advantageous position in the market, or self-preferencing practices – and to fine companies after repeated violations of these established rules.

“CMA’s weaknesses stand in stark contrast to Brussels’s recently approved Digital Services Act (DSA) that sets the rules for the first time on how companies should keep users safe on the internet.”

European lawmakers finalised negotiations on the DSA in April. The law will force tech companies to take more responsibility over the content posted on their platforms and significantly limit their ability to track user data.

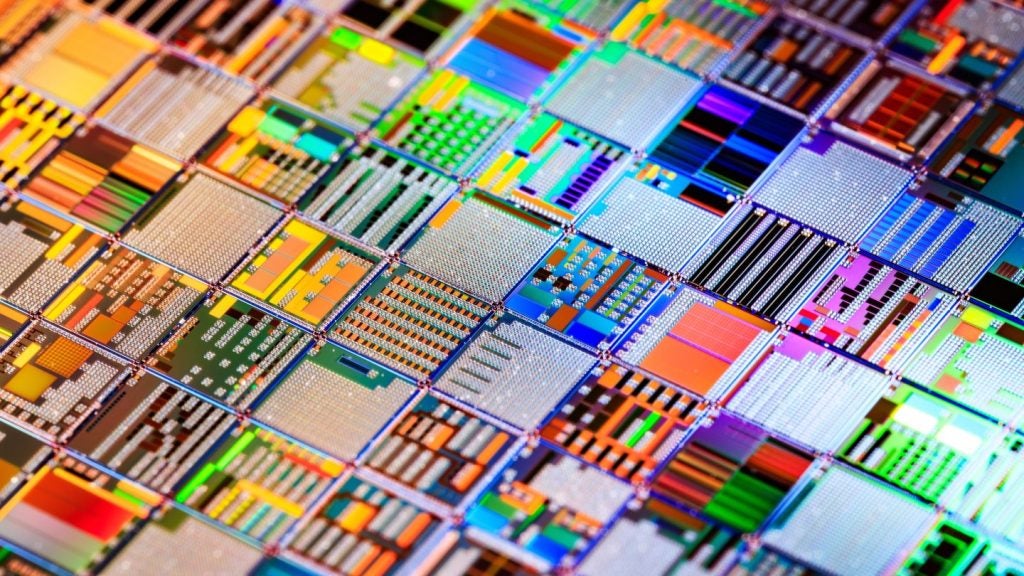

The CMA has previously launched antitrust probes against Apple, Google and Facebook. It was also one of several regulators around the world that expressed concerns against NVIDIA‘s plans to acquire semiconductor company Arm. The deal imploded earlier this year.

GlobalData is the parent company of Verdict and its sister publications.