How often do you think of leaving the UK for green pastures? Better job perhaps, higher pay, better living quality, cleaner air?

Second question: how likely are you to actually do it?

Consultancy Deloitte has been looking into this, specifically how non-British workers in the country feel about their prospects here after the UK voted to leave the European Union.

In their first Power Up report, high- and low-skilled foreign workers both in and out of the UK were asked a series of questions to find out how many were thinking of leaving and what it would take for them to stay.

The answers they received herald both opportunities and challenges for British business.

Headline figures out of the way first.

The report finds 36 percent of non-British workers currently based in the UK are considering leaving in the next five years.

Among high-skilled EU workers the number increases; 47 percent said they might be gone by 2023.

Those in London are more likely to leave (59 percent) compared to outside. In the Northern Powerhouse region, for instance, it’s only 21 percent.

For those outside the UK the numbers are a little friendlier: 21 percent said they find the UK less attractive, compared to 48 percent of those based here.

These numbers look dramatic but the report also found the UK, widely perceived as a land of diversity and opportunity, is the most favoured global destination for foreign workers.

So those are the numbers, but what does it all actually mean? Is Brexit pushing our foreign workers away?

Maybe.

For Angus Knowles-Cutler, Deloitte vice chairman and author of the report, the really interesting material comes out when you peel back some of the numbers.

There’s a big spectrum that comes out. If you take people in low-skilled roles outside London; baristas in Birmingham or chambermaids in Cardiff; (the potential attrition rate is) actually very low. Only one in five say they’re even considering leaving in the next five years. If you think about it, that means it’s probably lower than our recent history.

This makes sense for the low-skilled sector, who are in less demand and command lower wages across Europe.

This also goes a long way to explaining the discrepancy between London and the regions. Brexit didn’t cause demand for high-skilled workers in say tech and finance across Europe; that was already there.

But in combination with another non-Brexit related factor, that pull could get even stronger. Knowles-Cutler sees a clue in one of the questions his report asked.

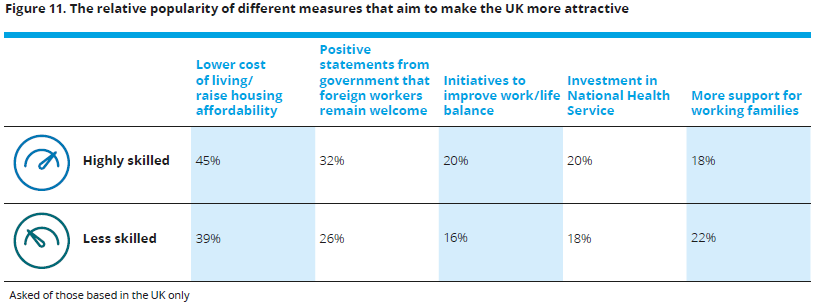

We asked ‘what would make you stay?’ The number two answer across the board was positive messages from governments but the number one answer was a lower cost of living, particularly in housing.

Working to live versus living to work

Nobody can quite agree which is the most expensive city in the world but there is no denying London, with all its charm, is high up there.

The high prices lead to harder work, more competitive labour markets and longer commutes.

For many people starting or mid-way through their careers that’s perfect; a place to work hard, hone your skills and get ahead; but for those who can afford to leave for say Frankfurt, Amsterdam or Madrid the lure of cleaner air, quieter roads and less-crowded schools will always be there.

Brexit is sure to have had an impact, of course.

With foreign workers still unclear one year after the vote exactly what their rights and immigration status will be in a few years it would be lunacy to suggest they’re not going to be weighing their options.

There is also the emotional factor: everybody with foreign friends in the UK (so, everybody) will anecdotally have heard of the shock, disappointment and hurt felt by those who had emigrated and set up a life here, or who were planning to do so.

That’s of course a hard thing to measure and for the purposes of this report Deloitte have avoided that question.

It does highlight, though, that the numbers in this report are not gospel; so much of it could be down to feelings, and feelings change.

We don’t know how many of these people surveyed will actually leave the UK because frankly the majority of they themselves don’t really know.

A couple I go to the movies with every week are not sure they’ll be staying.

Both Spanish (well, one of them is Catalan), they rank among the 47 percent of high-skilled workers who are seriously considering leaving.

They are hurt and resentful of the UK’s decision and while both have good jobs neither are sure they could be bothered with the hassle of it.

They have a house in Madrid, close to their families and old friends, and neither of them will stop going on about how relaxed and carefree the life is in Spain compared to here.

And yet I’ve spoken with them many times on this and they just don’t know.

They kind of want to leave but that doesn’t mean they will. Who knows what opportunities their sectors — banking and media — will offer them in the future, and while they’re still pretty angry even now you just can’t stay mad forever.

The lower negative perception outside of the country might also lend itself to this idea; people whose economic and career prospects are just as affected by Brexit but who weren’t here to actually live it from within might be less inclined to take a dim view of the decision.

All this can make it unclear how to take a report like Deloitte’s.

Knowles-Cutler, the author of the report, will be the first to say he doesn’t think 47 percent of EU workers will leave, that’s not what the report is for.

It is what it is. It’s an opinion poll if you like, it’s sentiment. The fact is, in the six years up to 2016, people left at the rate of around five percent a year. That’s not surprising on average, so that’s a churn of a quarter of that working population as the historical base.

For Knowles-Cutler the report isn’t some dire warning of a catastrophic attrition rate.

It’s a guide for businesses, a tool to help them know what their employees are thinking and give them a greater ability to adjust to the changes coming, however great or small.

Probably chief among these concerns is holding onto talent.

How do you keep people on board when they feel their own ship might be sinking?

Knowles-Cutler analogised it to what companies need to do during mergers and acquisitions, which produce a similar kind of instability to that felt in the wake of Brexit.

Well before you announce the deal, you’ve got to have plans in place to say, ‘Who do we need to stay?’, ‘What messages (do we) give out?’ and ‘Do we need to pay them more money?’; ‘Who do we need to get our arms around?’ And then you have to act really quite quickly.

The key to this is, as in most relationships, communication.

One of the more surprising figures in this report is that over half of all respondents said their employer has left them in the dark on what happens to them after Brexit.

This also could go a long way to explain the desire to leave and if there are any warnings to be found in this report it is that a lack of action and clear lines of communication will assure talent attrition.

Knowles-Cutler continued with his analogy:

One of the key axioms in mergers and acquisitions is it’s your best, brightest and most agile who will get the CVs out first and I think (the current situation) is a little bit like that. The clock started ticking in June last year and the more uncertainty prevails, the more likely you are to see people leave. Anecdotally it does already seem to be happening, there are increasing skills shortages in some sectors.

Skills shortages are the real worry for the UK, of course. Headlines such as: 96 percent drop in EU nurses applying to NHS, tend to make the eye twitch, and a lot of us are worried the UK will fall behind as a leader in growth and innovation.

Every sector’s got its own Brexit issue. If you talk to a retail CEO, he’s got some issue that is specific to supply chain from Europe and the fall of the pound. If you talk to somebody in banking, he or she needs access to the European markets. So they’ve got quite different (concerns) but there’s one thing they’ve all got in common, everybody’s very worried about a skill shortage. That permeates, whether it’s retail or professional services, financial services, creative, tech, transport – it’s people.

Skills shortages are a totally valid concern but it’s another one you can’t just put down to Brexit.

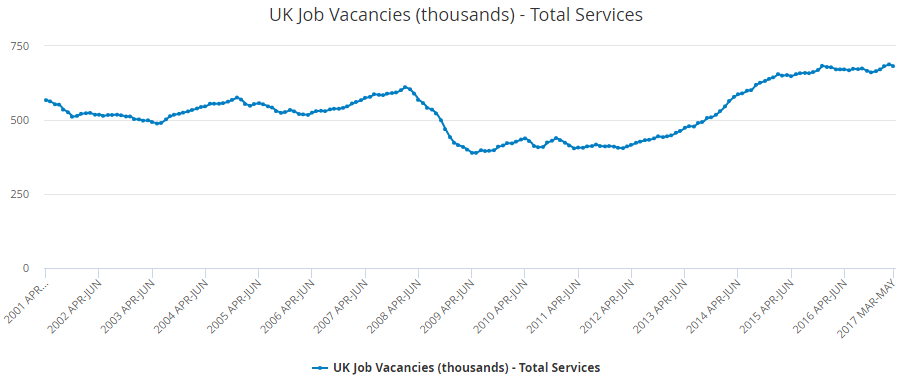

There are around 700,000 job vacancies in the United Kingdom, according to the ONS. This time last year it wasn’t much less than that. We already have a skills shortage.

Click to enlarge

Brexit didn’t cause that, but it could exacerbate it.

Knowles-Cutler said:

We’ve got more jobs than people. We’ve got record levels of employment, so it’s not as if there’s a bunch of people who can work who are waiting to fill vacancies. That’s just the reality of where we are.

He said in the event of a middling-to-mass exodus of foreign hands, the best path for companies involves two things. First, as mentioned above, is figuring out a Brexit strategy; who you need and how you keep them; and second is seeing what other resources can be brought in to make up the shortfall.

It’s a balance of retaining people you need now, (while) keeping the door open selectively, under controlled immigration status, to people you need to fill the gaps. That’s sort of giving you time if you’re a business, to really take a look at using tech more to increase labour productivity.

This includes automation in such fields as transportation and storage, accommodation and food services, and wholesale/retail trade.

Knowles-Cutler said we wouldn’t need to wait to implement these technologies if skills shortages began to bite.

It’s not just waiting for things five or ten years from now, there’s a lot of available technology that just hasn’t been implemented, probably because we had a ready supply of willing and able labour and some of that is migrant labour.

The other side to tech is the so-called up-skilling of British workers, vanishingly less likely to leave the UK.

This is an area where governments will need to shoulder more of the burden, if they get time away from Brussels.

From the report:

The rising number of high-skill jobs the UK is likely to have to fill from domestic sources will require more than a technical education: policies aimed at fostering high-level skills will have to reflect the primacy of cognitive abilities if the economy is to match its potential.

The cognitive abilities here are things like customer and personal service knowledge, oral comprehension, listening skills and critical thinking.

These are some of the skills the country needs to maintain and develop further to weather the storm, however bad it may be.

You’ll notice, these aren’t technical skills, these are people skills.

It’s many of these skills businesses would do well in using to get through Brexit. Ultimately it will be up to them to decide how they get ahead of the change, or if they do.

Knowles-Cutler pointed out most of the major increases in labour productivity have come after recessions, when executives are forced to adapt and upgrade. In the wake of 2008 many companies operating in survival mode found themselves implementing technologies that had been on the shelves for years.

This did not, however, mean the human workforce lost out.

Knowles-Cutler pointed to previous Deloitte research showing though technology has killed some 800,000 or so jobs in the last fifteen years it also created 3.5m new ones that pay on average £10k per year more.

Knowles-Cutler thinks businesses ought to be able to take advantage of this coming downturn, or whatever Brexit turns out to be for us, provided they remain open to adapting their technological and human capital, as his report recommends.

Hopefully it’s of interest to government but it’s primarily for our clients, because this has shot right up the agenda. It’s hard to have a conversation with a CEO or a business leader in the UK without this coming up. We’re 80 percent a service economy, and service economies tend to run on people.

And ultimately it is people who will be deciding how much of a success Brexit turns out to be, how well we weather the storm.

An essential part of this report — how people feel about Brexit — is incredibly hard to measure and what measurements are possible hugely open to interpretation.

But it certainly is felt.

Knowles-Cutler added:

Before we published (the report), I obviously wanted to check that we weren’t completely off the mark so I’ve taken it to a number of business leaders across different sectors. Nobody has said ‘this is not a concern’, ‘this is not something we’re actually seeing in our sector’.

I just texted my friends the Spanish couple. I asked them how likely it was, in a percentage, they would leave in the next five years.

About 45 percent.