It’s almost 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. We can still see the relics of the past throughout the city but many now say past divisions are barely noticeable.

How has Berlin’s relatively recent past affected its present, and how will it now shape the future?

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

Yesterday was the 28th anniversary since the demolition of the Berlin Wall. Each year in the country people reflect on the progression made in the city both economically and socially since the Wall came down, reviving the question of whether the divide between east and west still exists and what effect it plays on everyday life.

Popular consensus suggests that the division is still palpable, and various studies reveal an economic and political separation along the former line of the wall.

One sector — and one that arguably has become the city’s most important — seems unaffected by the wall’s lingering effects — that of startup companies.

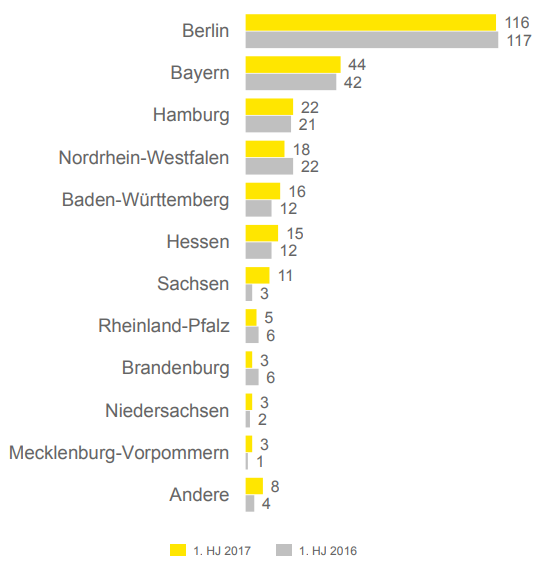

Venture capital investments in German startups hit a record level in the first half of 2017, with Berlin seeing a huge rise in funding for its startup scene, a report from accountant EY showed in July.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData

It found Berlin is the unrivalled startup capital of Germany with 44 percent of all investment deals happened in the capital — the size of Bavaria, Hamburg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Baden-Württemberg, and Hesse combined.

Paul Wolter of Bundesverband German Startups tells Verdict:

“When it comes to startups in Berlin, the divide between East and West is more or less not a factor. Maybe this was the case ten years ago when there was a bigger difference in housing or office rents. But not now.”

Berlin is the fastest growing startup ecosystem in the world.

Dubbed “poor but sexy” by its former mayor, the city has become a veritable hub for new businesses.

Its relatively low rents and “trendy” image make it a honeypot for young students and professionals.

This influx of youthful, international individuals means that it’s rapidly becoming a city populated by people who have little or no connection with its history.

Wolter adds:

There is a difference when it comes to those who lived here before the fall of the wall, people who were born and raised in different states and different economic systems and societies. But the people who came to Berlin after the fall aren’t going to see a massive difference.

For the younger generation, and for those not native to Berlin, the Wall is becoming less of a tangible memory, and more of a piece of history.

Berlin has changed rapidly since the late 1980s, now a liberal and creative hub it has become a site of development and forward-thinking.

Niko Woischnik, founder and CEO of startups Ahoy Berlin and Tech Open Air said:

The city is becoming more international by the day. Young, creative talent is abundant and there is a sense of optimism that is not very typical for older German generations.

It is a city shaking off the ideological baggage of the past and turning its gaze to the future, a future that is more stable and profitable if the city is united.

New startups are too young to have been affected by the upheavals caused by the Wall.

It is perhaps for this reason that startups are the most flourishing form of business in Berlin, considering older factories and companies endured the socio-political shifts caused by the revolution.

Michael Fischer, resident of Berlin for 38 years and member of mobility company Moia, says:

Most industrial companies left Berlin after World War Two and the old economy in East Berlin closed down after reunification. There was not a lot of positive vision in those years.

With the initial division of the city, some of the biggest firms moved their headquarters to more comfortable surroundings, leading to more progressive industrial developments happening in the west and ultimately causing the east to lag behind.

“After the fall of the Berlin Wall, formerly communist eastern German companies and factories suddenly had to compete with their much more efficient western counterparts”, writes The Washington Post, “capitalism came too fast”.

The east threw itself into rapid development to keep up with the west. This rush towards capitalism has receded but social and economic imbalances remain.

The sense of unity that seems prevalent in the city centre seems to significantly diminish at its outskirts.

Fischer says the inner city “is totally gentrified and the population in some parts has been almost completely replaced since 1989. But if you go to the outskirts of old East and West Berlin you still recognise differences in the way people think about their city, the economy, politics and the future.”

Reiner Klingholz, director of the Berlin Institute for Population and Development tells the Guardian newspaper:

The citizens of east and west were socialised in such a different way that in retrospect the idea that integration would be swift was utopian. This reunification was, and continues to be, far more difficult to achieve than was thought during the exuberance of the reunification celebrations.

A study Reiner’s department conducted in 2015 concluded that half of all Germans believe there are more differences than similarities between easterners and westerners than commonalities.

Similarly, a Statista poll published at the anniversary of the Wall’s fall last year found that only 50 percent of Germans perceive the east and west as united, while specifically in the east this figure falls to 43 percent.

The same survey found that 66 percent of Germans saw persistent signs of division in certain areas.

Markus Grabka, an economist with the German Institute for Economic Research has noted significant differences in the average net worth between eastern and western Germany, as well as imbalances in property quality.

As owner-occupied property is quantitatively the most important form of asset in Germany, the disparity is significant.

Lower income levels in the city’s east mean that households take on substantially more debt in order to acquire property.

The result of this is that the net worth of housing in eastern Germany “continues to trail the comparative figure in western Germany”.

Although there was a rapid series of improvements made in owner-occupied property in the east in the 1990s, the process has ground to a halt since the start of the 2000s.

Distinctions between east and west can also be seen from a political stance.

Woischnik says:

The integration of the East is still a challenge — and the current political shifts reflect that.

Meanwhile, the recent German elections in September of this year revealed that Berlin remains politically divided along the line of the Berlin Wall.

This fault line between the sides saw the ascension of a far-right party (the nationalist, anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany) into the national Parliament for the first time in almost six decades.

In comparison Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Social Democrats (SPD) saw their popularity sharply decrease.

While the Western boroughs have as a whole voted for either CDU or SPD, the largest number of electoral districts in the east voted for leftist party Die Linke.

Additionally AfD gained a significant number of votes in the eastern suburbs.

Many attribute it to the economic decline of the east and the anti-left views that gained popularity after the fall of the wall.

While few wanted a return to communism, many were also disillusioned by Western capitalism and right-wing politicians were quick to fill this gap.

Website Citylab reports the rise in AfD support is partially due to its provision of “a political outlet for the curdled political frustrations of easterners who feel left behind and seek a cultural enemy – outsiders – on whom to vent their anger”.

Berlin is expected to become an even bigger base for business in Germany.

Fischer says he expects Berlin to become “the IT and mobility hub in Germany” adding

Hopefully big venture capital firms and incubators like Rocket Internet will become essential for the city. I truly believe that Berlin will become the most important location for big international mobility players.

Woischnik predicts:

The tech and startup industry will continue to grow with more capital flowing into Berlin. German corporates are waking up and while it may be too late for some, the interaction with startups can lead to fruitful results for both.