Don’t laugh. It may sound like a bad joke, but Google and Apple are trying to rebrand themselves as privacy crusaders. And it’s no mystery why: they have no choice.

A number of high-profile privacy scandals have turned the public against the notion that tech companies should be allowed to stalk people online willy-nilly. Lawmakers are responding to the demands of the public by working to curtail the power of Big Tech.

“I think both companies foresee a future in which governments restrict the collection, use, and sharing of personal information, and a majority of their users will support those restrictions,” Paul Bischoff, privacy advocate at Comparitech, tells Verdict.

This is unsurprising. Data privacy is growing increasingly important for companies. Regulators, politicians, investors and consumers are paying more and more attention to the way that businesses protect private information – or don’t – as highlighted in a recent GlobalData report.

Big Tech has listened. During an investor conference call this week to discuss Apple’s third quarter earnings, CEO Tim Cook said: “Privacy is a fundamental human right.”

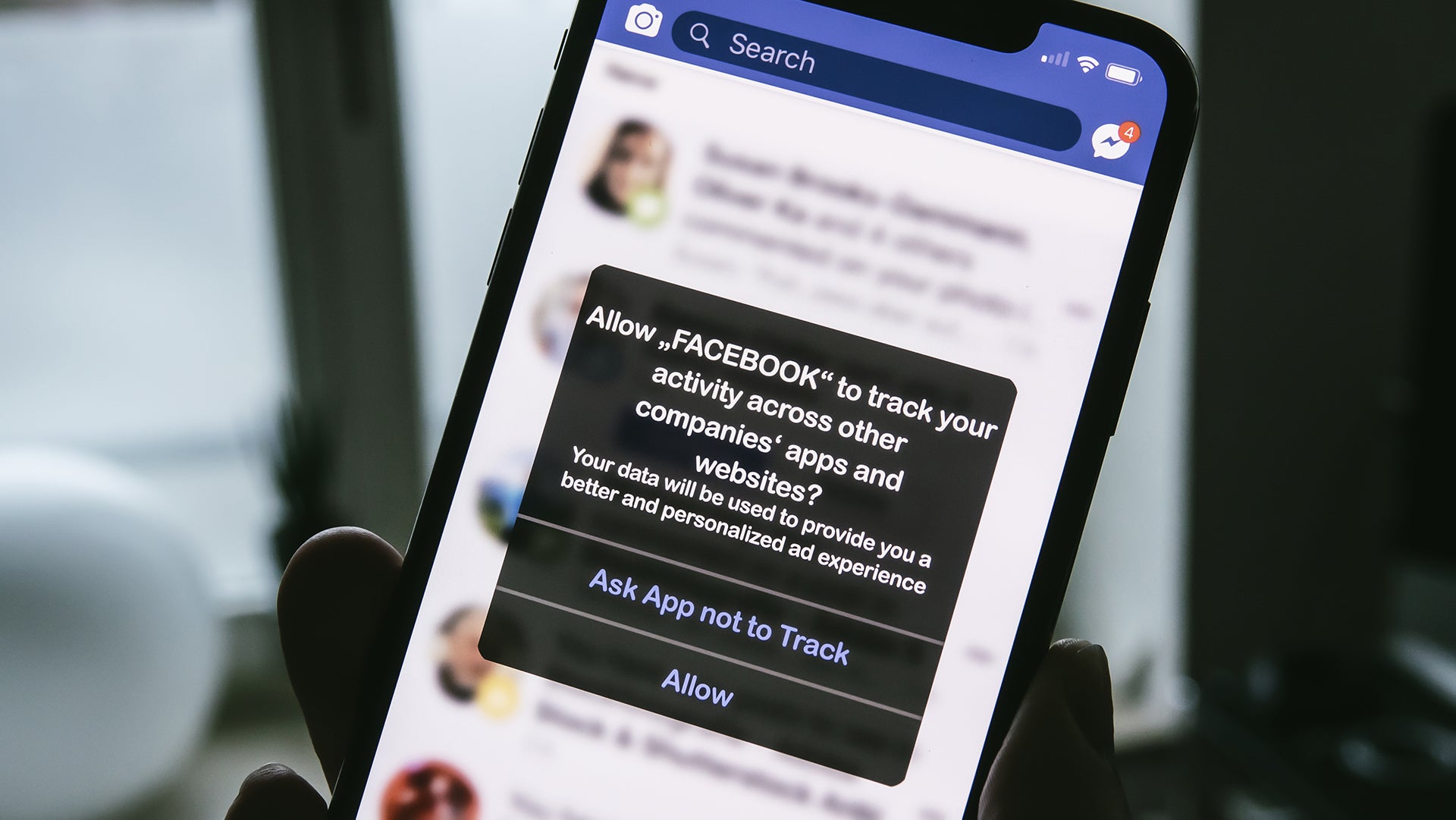

This follows from the Cupertino-headquartered company’s recent iOS 14.5 update that enables iPhone owners to turn off apps’ ability to track them.

Google has, on its part, this week updated the timeline for the rollout of its Privacy Sandbox – its project intended to rid the web of third-party cookies able to stalk users online. Google can achieve a huge amount in this area if it wants to, due to the popularity of its Android mobile software and Chrome browser.

Nevertheless, the notion that the two Silicon Valley giants would suddenly turn on their heels and become privacy bastions is probably going to elicit a raised eyebrow or two. After all, both behemoths have been embroiled in several privacy scandals over the years.

In 2018, for example, Google revealed that a bug in the now-defunct social media platform Google+ had compromised 52 million accounts. Apple, for its part, has faced scrutiny for allowing developers to eavesdrop on users’ conversations with the smart assistant Siri, for tracking iPhone users’ movements, and for the so-called “fappening” event when a hacker broke into several Hollywood actresses’ iCloud accounts (among others) and leaked private videos and photos to the public.

Both Apple and Google are seemingly trying to rid themselves of the memories of these data privacy disasters. So does that mean that the two tech titans will truly stop tracking users?

“Not at all,” argues Bischoff. “Both Apple and Google still have a lot of ways to track you, especially for internal purposes. Their initiatives just lessen the amount and specificity of tracking. It’s a compromise, not an abolition of tracking.”

No wonder, then, that responses to these initiatives have been mixed. On the one hand, privacy advocates have welcomed the push towards boosting protection against companies and state actors tracking internet users.

On the other, Google and Apple have been criticised for not doing enough to protect people’s privacy and for flagrantly trying to capitalise on public opinions against data tracking with so called “privacy washing.”

“Privacy washing is a deliberate attempt to invoke privacy to help a brand, but not actually deliver privacy to consumers,” Gabriel Weinberg, founder and CEO of DuckDuckGo, tells Verdict.

The mixed response can also be attributed to Google and Apple’s initiatives being very different. The difference between them is there for obvious reasons: they are not the same kind of company.

“You are talking about two industries that have very different monetisation systems,” Heather Anson, managing director of data protection consultancy Anson Evaluate, tells Verdict.

Google is, at its very heart, an advertisement business whereas Apple is a device-driven company. So when they are talking about how they protect people’s privacy, they’re talking about very different things.

Google crumbles third-party cookies

Third-party cookies are central to Google’s privacy initiatives. The name refers to little strings of text that have had a huge impact over the years.

Up until now, they’ve been central to advertisers’ ability to stalk people across the web. They differ from first-party cookies that only track visitors within individual websites. Those tools basically just keep an eye on things that happen on that site, such on the content of shopping baskets.

Third-party cookies, on the other hand, will follow people around when they scuttle off to other sites. If you’ve ever wondered why ads about the t-shirt you glanced at for two seconds several weeks ago keep popping up every time you go online, third party cookies are the answer.

Now, Google is planning to ditch third-party cookies on its Chrome browser from 2022. Mountain View announced the plans in January 2020, saying it was time for people to regain a sense of privacy. First-party cookies would still be allowed. Market stakeholders welcomed the move with cautious optimism.

“It’s a real opportunity to improve the privacy properties of the web,” Marshall Erwin, senior director of trust and security at Mozilla, tells Verdict.

Not the first cookie monster

Google isn’t the first company to block third-party cookies on its browser. Apple limited cookie-tracking on its Safari browser in 2017. Mozilla’s Firefox did the same in 2019. Other browsers like Brave and Vivaldi block third-party cookies as their default mode. Still, with 2.65 billion Chrome users around the world, the Mountain View-headquartered firm’s block will arguably have the biggest impact yet.

Feeling sceptical over the notion of the search engine colossus suddenly becoming a crusader for internet anonymity? You’re not the only one. Despite the initiative having been recognised as a step in the right direction, the move has also been criticised for potentially choking competition and for actually doing very little to guard against online tracking.

Describing what Google is doing gets technical really fast, but the key thing to remember is that Mountain View has no intention of putting an end to online tracking.

Doing so would take a massive chunk out of Google’s quarterly advertisement revenue – which rose nearly 70% to $50.44bn during the second quarter ended June 30. That’s almost five-sixths of the total $61.88bn revenue going through Google’s books during that period. To put it bluntly: Google would be insane to kill a cash cow like that.

Instead, Google is replacing the old system with a new one referred to as the Privacy Sandbox, championed by Mountain View as a way to create new advertisement tools with privacy at their heart and enabling users to fight back against sites using hidden or opaque techniques to secretly track and share user data.

Google’s Privacy Sandbox

The segment of the Privacy Sandbox that has come under the most scrutiny so far is called Federated Learning of Cohorts, or FLoCs. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) has branded the application programming interface (API) for FLoCs the “most ambitious and potentially the most harmful” of Google’s new proposals.

“The FLoC proposal is a privacy-preserving API centred around cohorts in a browser i.e groups of users who have similar browsing behaviours,” a Google spokesperson tells Verdict. “Privacy is attained by only revealing the cohort ID and not individual user IDs; so individual users are indistinguishable within a single cohort.”

Mountain View claims the API will ensure personal browsing history doesn’t leave users’ browsers or devices. Theoretically, this means it won’t be shared with advertisers or anyone else.

“FLoC is based on large anonymous groups, not tracking individuals across the web as third-party cookies do today,” the spokesperson says.

It is unclear how large these groups will be. Google has proposed that a central actor could count the number of users assigned to each cohort, ensuring that they’re not too small and therefore enabling members to be identified.

This could enable Google to track thousands of people and even anticipate what people would be interested in. If there are two people in this group who really like, say, Marvel movies, it stands to reason that a third person in the group would be interested in watching the new Black Widow movie too. Advertisers could thus target the group with appropriate ads.

Google has argued that FLoC is just as capable at tracking users as third-party cookies. Or at least really darn close.

“Our tests of FLoC to reach in-market and affinity Google Audiences show that advertisers can expect to see at least 95% of the conversions per dollar spent when compared to cookie-based advertising,” said Chetna Bindra, group product manager of user trust and privacy at Google, earlier this year.

Adtech experts have expressed scepticism about this claim, saying that they’d have to see it before they believe it.

No matter how efficient these tools will be, it still means that Google will continue to track Chrome users and that advertisers can still cough up cash for targeted ads.

Competition concerns

So, at least the advertisement industry should be happy then? Well, not quite. Instead of sighing in relief, they are worried that Google would simply use the FLoCs to further entrench its dominant market position.

In response to these concerns, regulators like the UK’s Competitions and Markets Authority (CMA) and the European Commission, have opened investigations into Google’s plans to cut off third party cookies.

“We are concerned that Google has made it harder for rival online advertising services to compete in the so-called adtech stack,” Margrethe Vestager, executive vice-president at the European Commission, said in June when opening the probe.

The investigation would also look into the matter of Google possibly breaking EU competition rules by favouring its own online display advertising technology services.

Google has said that it will collaborate with both investigations. In response to the CMA probe, Google committed itself to playing “by the same rules as everybody else” in June, adding that it wouldn’t “give preferential treatment to Google’s advertising product or to Google’s own sites.”

Google also pledged to continue to communicate with the CMA and to not build any alternative identifiers to track individual Chrome users.

“The commitments confirm that we will play by the same rules as everybody else because we believe in competition on the merits,” a Google spokesperson says. “Our commitments make clear that, as the Privacy Sandbox proposals are developed and implemented, that work will not give preferential treatment or advantage to Google’s advertising products or to Google’s own sites.”

The CMA is currently reviewing these pledges. If given the thumbs up from the markets watchdog, Google has said it would roll out the same standard across the globe.

Privacy Sandbox’s privacy problems

The FLoC system has also been criticised over the way it would group together different individuals. One risk, voiced by Firefox distributor Mozilla among others, is that grouping together people with interests and behaviours could mean that the API could inadvertently identify them as people with characteristics such as gender, race and sexuality. The ads could end up reflecting this in a discriminatory way.

For instance, a cohort that consists only of people who visited Grindr Web could accidentally be identified as consisting of gay men.

Google has responded to these fears in a white paper. While overflowing with technobabble, it essentially boils down to Google committing itself to identifying and creating a blocklist for sensitive cohorts to avoid them being used to discriminate.

“Our FLoC analysis evaluated whether a cohort may be sensitive without learning why it is sensitive,” a Google spokesperson says. “So cohorts that reveal sensitive categories like race, sexuality, or personal hardships are blocked or the clustering algorithm will be reconfigured to reduce the correlation. It is also against our advertising policies to serve interest based ads on these sensitive categories.”

Google does admit that the approach does have its limitations and setbacks, agreeing that “calculating the sensitivity of the cohorts itself raises privacy concerns for users, since it requires access to their browsing history”. Mountain View also argues that this measure must be balanced with the degrading utility of blocking too many cohorts.

Mozilla has warned these measures may prove inadequate protection against FLoC-based discrimination because the list of sensitive categories is incomplete and doesn’t involved related sites that aren’t deemed to be sensitive. Moreover, the Firefox developer feared “clever trackers may be able to learn sensitive information despite these controls.”

Another concern, raised by the likes of EFF, is that FLoCs would do little to prevent fingerprinting. This refers to the practice of gathering unique pieces of information about users’ devices – such as their screen size and how they behave – to create a unique profile.

“While notionally third party cookies will be blocked, what this is doing is actually making it easier to fingerprint you,” Erwin claims, arguing that grouping people together in cohorts means “it actually makes you the more uniquely identifiable.”

Unsurprisingly then, several internet stakeholders – such as privacy-focused browser Brave – have already openly blocked FLoC from their services.

“The worst aspect of FLoC is that it materially harms user privacy, under the guise of being privacy-friendly,” Brave argued in a blog, claiming that “FLoC shares information about your browsing behaviour with sites and advertisers that otherwise wouldn’t have access to that information.”

Similarly, privacy-focused search engine DuckDuckGo has also barred FLoC, accusing Google of privacy washing.

“Google has made this part of their communications toolkit, claiming at their latest developers conference their products have ‘privacy by design’ but it was limited to privacy controls rather than actually making a meaningful change to how much data they collect in the first place,” Weinberg says. “We think ‘misleading by design’ might be a more accurate description.”

Mountain View clearly faces a challenge in convincing people over its sincerity in championing privacy. Apple, on the other hand, has a slightly lower obstacle to overcome, mostly because it’s been working on its brand as a privacy guardian for years.

Apple bytes back against tracking

Tim Cook was not happy. In September 2014 the Apple CEO published an open letter seemingly condemning many of his fellow Silicon Valley companies for treating users’ privacy as their own personal money farms. But change was coming.

“A few years ago, users of internet services began to realise that when an online service is free, you’re not the customer. You’re the product,” Cooks wrote. “But at Apple, we believe a great customer experience shouldn’t come at the expense of your privacy.”

Cook’s message was clear: Apple wouldn’t do anything to compromise users’ privacy, whether by stalking them online or by providing state agencies with the means to spy on citizens.

The letter was also a poorly veiled jibe against rivals like Google and Facebook who may be offering a free service, but only at the expense of the data they can harvest from customers.

While the Cupertino-headquartered company had previously made similar statements, it was the unofficial launch of an almost decade-long campaign where Apple has positioned itself as a champion of people’s privacy.

Since then it has doubled down on the protection of users data, going as far as refusing the FBI’s demands to hack into the iPhone belonging to one of the San Bernardino mass murderers. An Australian firm did the job after Apple refused.

Despite that, Apple has been accused of hypocrisy. The allegations were somewhat deserved as Apple allowed iPhone apps to collect data on users without customers having any say in it. In return, Cupertino got a 30% cut of all the profits made by the services on the App Store. But it seems as if those days are coming to an end.

Unfriending Facebook

Things moved up a notch at the end of 2020 when Apple announced the new iOS 14.5 update. The iPhone operating software would enable smartphone owners to block apps from tracking what people were looking at outside of the apps.

This was the cue for Facebook to panic. It’s no secret why that was. As CEO Mark Zuckerberg said during a 2018 congressional hearing when asked how Facebook remains free to use: “We run ads.”

So, when the iPhone maker announced it would empower iPhone owners to block tracking, it meant companies like Facebook would be at risk of losing out on one of its biggest sources of revenue. Without the data, targeting ads would suddenly be much harder.

Unsurprisingly, Facebook fought back by taking out ads in New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Washington Post, accusing Apple of threatening the livelihoods of the “10 million businesses [who] use our advertising tools each month to find new customers, hire employees and engage with their communities”.

In March, it was also revealed that the Beijing-backed China Advertising Association (CAA) planned to launch a tool that would enable its 2,000 members, which include Tencent and ByteDance, to circumvent the transparency feature. The iPhone maker didn’t reply directly to the news, but warned that apps “found to disregard the user’s choice will be rejected” from the App Store.

Apple subsequently followed through with its threat and blocked several of these companies. In the aftermath, the Financial Times reported that the CAA lost its support.

Similarly, on the other side of the Pacific, Facebook begrudgingly agreed in the end to update its iOS app to enable the new app-tracking transparency feature.

Did it hurt ads?

Surprisingly, people haven’t necessarily denied apps from tracking them as much as the adtech doomsayers expected. Contrary to reports about it being the end of tracking, attribution platform AppsFlyers’ July report on the impact of AppTrackingTransparency policy estimates that 45% of people were okay with being tracked when prompted by Apple to give their consent.

Nevertheless, advertisers have fled from the Apple ecosystem in the aftermath of the implementation of iOS 14.5 and its subsequent updates. By July, they spent 15% less overall on Apple’s smartphones. Interestingly, gaming apps stood out from the rest with their iOS budgets actually increasing by 21%.

That being said, during the same period gaming apps’ Android expenditure jumped by 31%. While it may be too early to say if this is a trend or not, gaming apps were among the first to adopt Apple’s App Tracking Transparency policy and could there potentially be seen as a precursor of things to come.

It’s no secret why the iPhone maker decided to curb the tracking of its users. Ads only make up a marginal part of its business. Instead, the company makes most of its money through sales of iPhones, Mac, iPads and its different wearables and accessories. In other words, it’s fairly simple for Cupertino to get its priorities straight.

“Apple uses privacy as a competitive differentiator,” Gabrielle Earnshaw, mobile subject matter expert at Infinity Works, tells Verdict. “It has built consumer trust over the years, and its customers are prepared to pay more for its products and services in return for having higher levels of privacy protection.”

And it’s not stopping. In June, the iPhone maker held its annual Worldwide Developers Conference. As usual, the company unveiled a smattering of new features and services, including new AirPod and Apple Wallet features.

One thing became clear among the announcements about the new features and the upcoming iOS 15, iPadOS 15, macOS Monterey and watchOS 8 operating systems: Apple is making privacy even more central to its products. Not only did almost every announcement include a line or two about how privacy would be at the heart of the products, but Apple’s privacy was also given a presentation of its own.

Sincere or not, it is clear that Apple will continue to flog its phablets on the notion that it is protecting users’ privacy – especially since public opinion looks set to continue to turn towards more privacy.

Changing public opinion

People don’t like being followed around. That’s as true online as it is offline. And over the past few years they’ve grown increasingly vocal in their protests. A series of high-profile scandals has contributed to the shift in public opinion.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal provides a good example. In the early 2010s, the British consulting firm had collected information about 87 million Facebook users without their consent, subsequently subjecting them to targeted political ads. As a result, the consultancy has been accused of having manipulated the outcome of the 2016 US presidential election and the Brexit referendum. Cambridge Analytica was forced to shut down in the aftermath of the revelations.

Target provides another example of how these things can go wrong. In 2012, the New York Times published a story about a man who’d entered one of the American retailer’s stores. He was furious, demanding to know why Target had sent coupons for baby clothes and cribs to his teenage daughter.

As it turned out, data collected from her online history had correlated with patterns from other expecting mothers. When asking his daughter, the man found out that she was indeed pregnant. In other words, data tracking had outed her pregnancy before she’d had a chance to tell her parents.

“As one commentator said: “It’s not illegal, but it is kind of creepy,’” Anson says.

Data tracking has also been accused of being a discriminatory tool. By collecting data on people’s interest as well as their geolocation and address, they could be identified as belonging to different minorities.

“That data is then used to target ads in a way that might be discriminatory or target ads to you in a way that might be misleading or identify you as a particular segment of society that is particularly vulnerable to a particular message,” explains Erwin.

In 2019, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development sued Facebook over the way it let advertisers purposely target their ads by race, gender and religion. The regulator took particular issue with Facebook allegedly giving advertisers the ability to exclude different groups of people from seeing flats and houses. Facebook said it would stop providing the service. In 2020, Google made similar commitments to clamp down on discriminatory housing and job ads.

Following these scandals, 72% of Americans understandably worry about being tracked online by advertisers, tech firms and other companies, according to public opinion polling from Pew Research Center. The research was later cited by Google when Mountain View justified nixing third-party cookies.

At the same time a number of new regulations, such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), have been introduced to protect people’s data and to give them more control over how their information is used. Virginia has adopted a CCPA-like law and New York is considering it.

And new laws are inbound elsewhere. The European Commission is currently pushing its Digital Services and Markets Act through the corridors of Brussels. In the States, five federal bills are currently on the floor of the senate to curtail the power of Big Tech.

“All of those things have made people care about their privacy more, but also put pressure on companies – Mozilla, Apple, Google – all of us, to really much more proactively think about what we’re doing to protect our users,” says Erwin.

It is against this light that Google and Apple’s initiatives should be seen: as the giants protecting their bottom lines. Still, hesitant as people may be to wholeheartedly believe Apple and Google are truly bastions of privacy protection, most market stakeholders Verdict has spoken with have been cautiously optimistic.

“On a spectrum of ‘not private’ to ‘private’, these initiatives tip the scale slightly more toward the private side,” says Bischoff. “We could always be more private, but at some point, we as a society have to decide where to draw the line.”