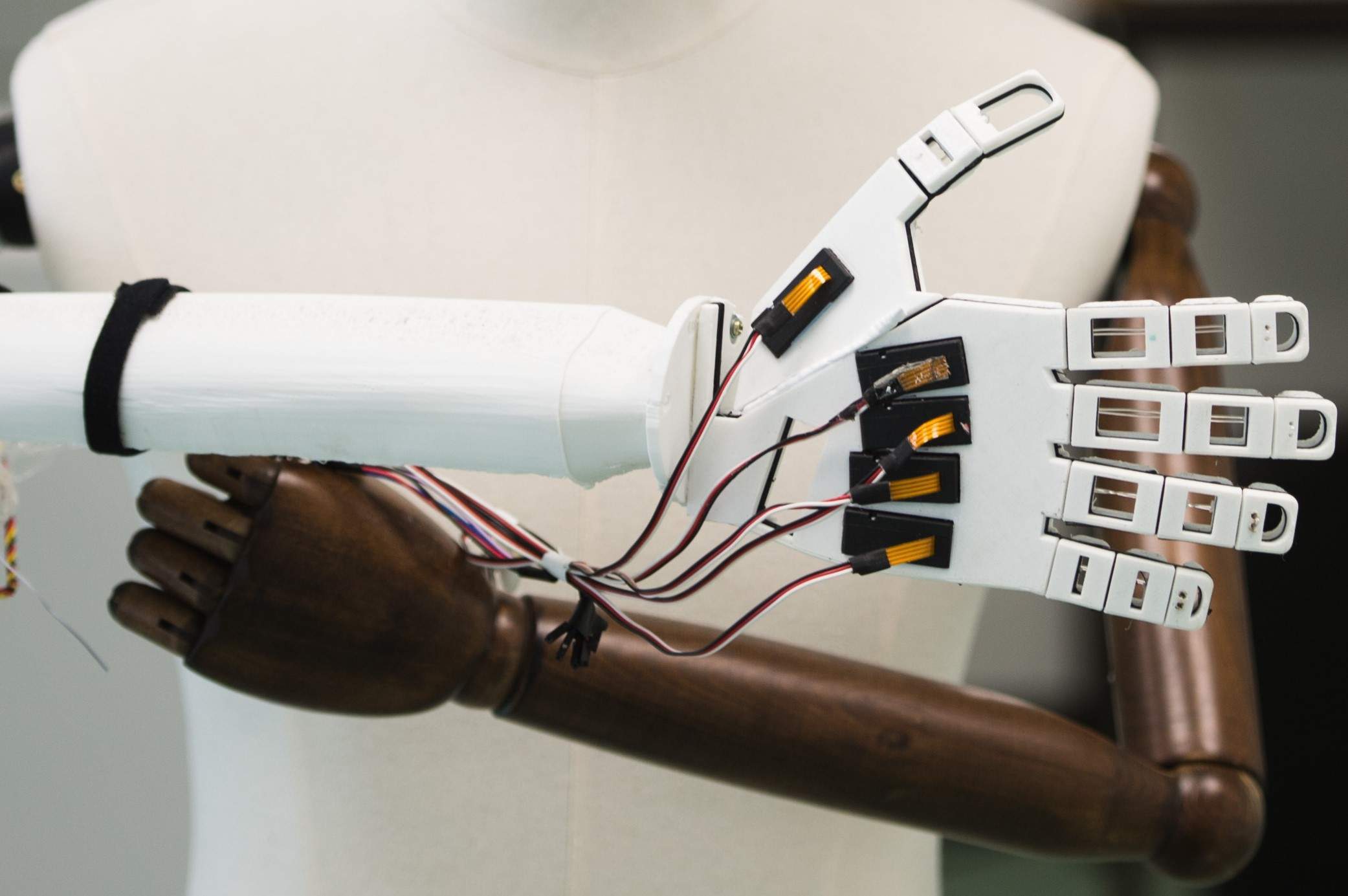

Scientists at the University of Glasgow are developing a synthetic e-skin that can mimic the sense of touch on a robotic hand.

The synthetic e-skin, also known as ‘brainy skin’, is being developed to make more responsive prosthetics for amputees. It could also be applied to robots to give them the ability to touch.

The e-skin can also detect temperature and mimics some features of human skin, such as softness and bendability.

How does it work?

The synthetic e-skin reacts in a similar way to human skin. When pressing an object against a human finger, there are a large number of receptors at the point of contact that send signals to the brain.

Professor Ravinder Dahiya, who is leading the research, said: “Human skin is an incredibly complex system capable of detecting pressure, temperature and texture through an array of neural sensors that carry signals from the skin to the brain.”

Dahiya looked to simulate this process in the e-skin, which is made from silicon-based printed neural transistors and graphene.

It gathers information from sensors on the highly flexible skin and converts the physical stimuli into a frequency. More force equals a higher frequency, and less force equals a lower frequency.

This information is relayed to the body via a non-invasive patch placed on the users’ body.

“The codes that are generated through tactile sensing, we convert them into vibrations,” Dahiya told Verdict.

If a hand is amputated at the wrist, for example, a patch on the shoulder will create vibrations that replicate the pressure placed on the robotic hand.

“We call this a sensory substitution. We are basically substituting our tactile feeling with vibrations,” said Dahiya.

Crucially, the synthetic e-skin only sends partial data to be processed. This ensures that the feedback loop isn’t slowed by the large amounts of sensory information that’s created when applying even the smallest amount of pressure.

The future of synthetic e-skin

Dahiya has used early versions of the technology in robotics, an industry which is expected to contribute £14tn to the global economy by 2035. Versions of the patch have also been used for communication between deaf and blind people.

The long-term aim is to create a neural interface, which is a direct connection between the brain and the robotic hand. However, Dahiya says that this is still about “ten to 15 years away.”

The project, called neuPRINTSKIN, has just received another £1.5m funding from the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC), a non-departmental public body funded by the UK Government.

Recently a team of engineers at Johns Hopkins University created an ‘e-dermis’, an electronic skin that provides prosthetic arms with a real sense of touch through the fingertips.